Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

When 50 students at Denver’s George Washington High School were flagged on a survey as having “extremely elevated risk” for mental health struggles, social worker Sarah Hartman was able to check in with all 50 and offer them services.

That’s a rarity given the bulging caseloads of most school social workers and psychologists, Hartman and others said — and it was only possible because Hartman is part of a pilot program launched in 2021 that originally added mental health providers to 10 Denver schools.

The program was aimed at helping the majority of students who don’t regularly see a school psychologist or social worker. Those providers are busy serving students with disabilities who are legally entitled to services, and they often don’t have time to help other students struggling with depression, grief, and the trauma of growing up during COVID.

Out of the 50 students to whom Hartman offered mental health services, only five said no.

“Kids would be like, ‘Miss, I have anxiety,’” Hartman said in an interview. “When you ask them if they want help, they want help.”

But that help could soon go away.

The pilot program is funded with temporary federal pandemic relief dollars known as ESSER. Because of a merger with an existing Denver Public Schools program focused on substance abuse prevention, the program has expanded to 31 schools at a cost of $3.4 million this year.

But the ESSER money is set to expire this fall, though federal officials recently announced a potential extension if districts spend it on certain efforts such as tutoring. Facing a likely funding cliff, the mental health providers are fighting to keep a program they see as fulfilling what had been an empty promise from DPS to do better on mental health.

Meanwhile, the district is evaluating whether it can afford to do so. A spokesperson said in a statement that the district “is examining the benefits / impact of programming for student outcomes, as well as feasibility to sustain programming as is.”

“How fair is it to identify a concern but then not have the resources to address the concern?” Joe Waldon, a social worker in the program at Hill Campus of Arts and Sciences, asked the school board Monday. “This is a huge ethical dilemma for me.”

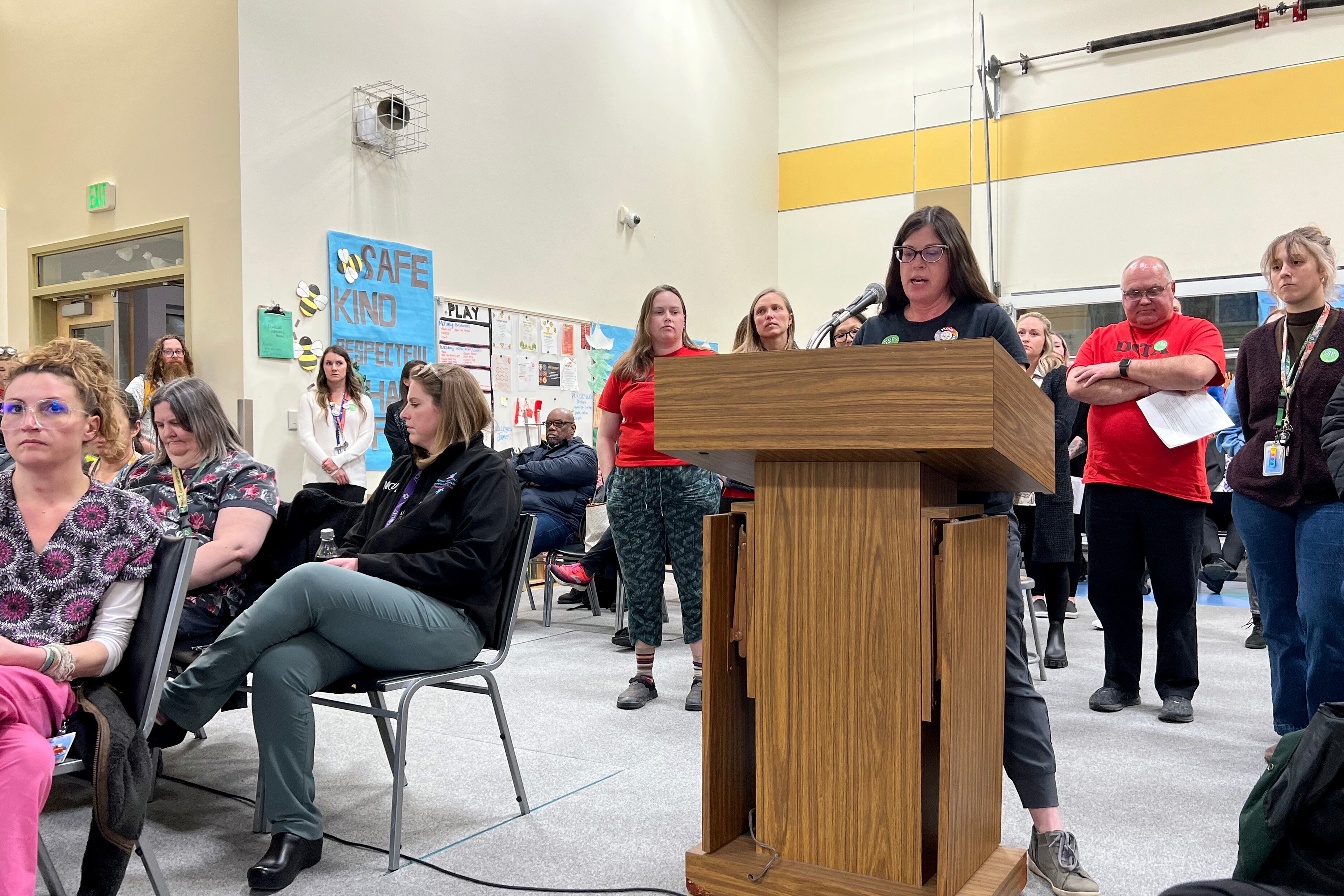

A cadre of providers in what DPS calls the prevention and therapeutic specialists, or PTS, program pleaded with board members this week to find sustainable funding once ESSER expires. They shared with them a spreadsheet of more than 100 supportive comments they’d solicited from other school psychologists and social workers, teachers, parents, and students.

“She helped me calm down when I was angry,” one second grade student wrote of the provider at their school, according to the spreadsheet, which was also shared with Chalkbeat. “She taught me to let my emotions out whenever I need to by crying it out, and that it is okay.”

A fourth grade student wrote that the provider at their school taught them about “safe touch and who is allowed to see private parts.” A fifth grader wrote that they spoke to the provider about their mom’s abusive boyfriends and addiction to drugs and alcohol. “She helped me work through all of those memories and experiences,” the student wrote.

A student at East High School wrote that if not for the counseling support they received, “I don’t know how much I would (have been) able to attend classes last year because of my anxiety.”

Maria Hite, a PTS social worker at North High School, has a box of fidget toys and a mini Zen garden in her softly lit office, where students can trace a tiny rake through the sand as they talk.

Hite and the PTS team at North “have supported students in a way that our school-based mental health team do not have capacity for,” an educator at the school wrote, adding that the traditional psychologists and social workers “are already drowning as it is.”

District statistics show that in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years, the PTS providers did one-on-one therapy with 415 students and group therapy with 783 students. More than 80% of those students were Black or Latino, and 83% came from low-income families — percentages that are higher than the district averages.

The providers also taught suicide prevention lessons to more than 2,400 students, and lessons on dealing with stress and anxiety or the dangers of vaping, drinking, and using drugs, to more than 17,000 students. If a student gets caught with drugs on campus, the PTS providers can provide counseling and intervention as an alternative to out-of-school suspension.

School psychologists and social workers are in high demand in DPS, and the PTS providers are not worried about finding jobs if the program ends. But they are worried that they will once again be pulled into the paperwork-heavy and crisis-heavy work of serving students with high needs and disabilities, and that the students they serve now will fall through the cracks.

Said Waldon: “How do you tell a child, ‘I don’t have time?’”

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.