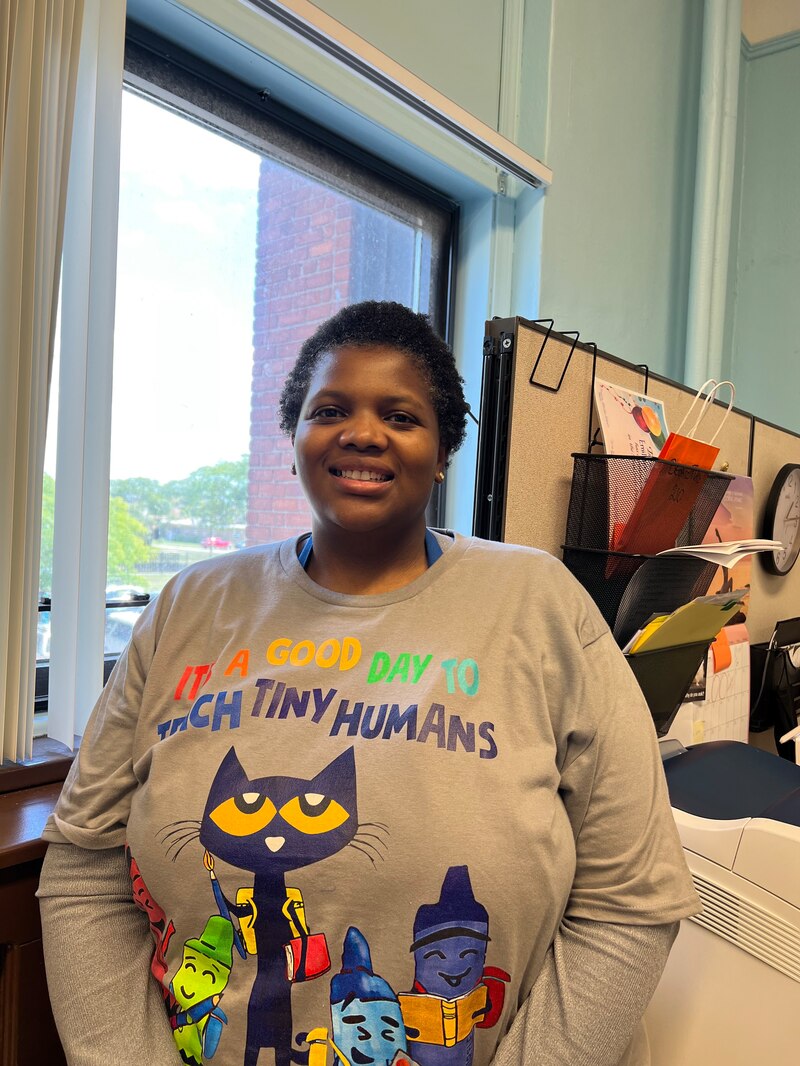

Spend an hour with Cheriese Gipson, and you can’t help but get a sense of what she’s like as a preschool teacher.

She starts to explain a favorite lesson about mittens and animals, then pauses, disappears off the Zoom screen, then pops back up with a puppet on her hand to continue the discussion.

After lunch, one of the 4-year-olds returning to Gipson’s classroom pokes her head onto the screen, wanting a hug and a look at whom Gipson is talking to. Speaking in Spanish, Gipson explains that she needs a few more minutes to wrap up the interview.

Asked how her name is spelled, Gipson declares that the public needs to know about letter links, which help preschoolers recognize how individual letters make the same sound in different words. It’s one of her favorite teaching tools. The “g” in Gipson is also used in “gladiolus,” her favorite flower.

Teachers like Gipson — experienced, committed to working with preschoolers, and bilingual to boot — are in short supply in Michigan. A yawning pay gap between preschool teachers and their K-3 counterparts has undermined hiring efforts for the Great Start Readiness Program, Michigan’s free, state-funded preschool, threatening Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s ambitious plans to make the program available to every 4-year-old in the state.

In a new budget proposal, Whitmer called for more GSRP funding and a $50 million investment in early educator recruitment and training. If she needed someone to pitch prospective teachers on preschool, she could do a lot worse than Cheriese Gipson.

After teaching other grades, Gipson returned to preschool.

“I like that beginner element,” she said. “I like the groundwork of creating the first school experience.”

Gipson has taught at the Cecil Early Childhood Education Center on the west side of Detroit for seven years. Her classroom is funded by GSRP and the federal Head Start Program. She studied education at Marygrove College in Detroit and received a master’s degree in early childhood education from Oakland University.

Chalkbeat recently spoke with Gipson about her favorite lessons to teach — and the most important ones she’s learned.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How and when did you decide to become a teacher?

I think probably at some point in grade school. I thought about being a [medical] practitioner, but I did not like the blood. When I was in high school, I was an exchange student. I got the chance to volunteer in a teaching setting, and I loved it.

Can you talk about how that exchange program impacted your work today?

It was in Central America [Honduras] through an organization called AFS. You spend a year in another country not only being a student but also being a part of the community. You live with someone, and you experience a variety of different things within those countries.

Originally, I didn’t speak the language. But once I was able to communicate more, I could navigate more, and I met people that owned a bilingual school, and I volunteered there.

(Gipson is bilingual in Spanish, a skill she uses every day to communicate with students from Spanish-speaking families.)

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received about teaching, and how have you put it into practice?

Be afraid, and do it anyway. When you start teaching, everything is brand new, every school year is brand new.

Whether it’s the beginning of the week or the beginning of the year, everything has newness to it.

We’ve had a variety of children with disabilities, and the majority have never been in any other school setting before coming to us. We’re some of the first observers and assessment people besides doctors and families who are telling parents what we can help with and what they can do.

Sometimes we go through a lengthy paperwork process to get children [support] and ultimately find the best fit location for them, whether it’s Starfish or somewhere else.

You love the children to the point that you don’t want them to go, but sometimes your classroom is not the best place for them.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

So recently, we did a story — hold on, let me get a glove, and I’ll show you exactly. (Gipson steps off the screen and reappears holding a mitten.)

Our children love listening to stories, but they love more than anything that they get to participate in.

This week, we did an interactive story called “The Mitten” [by Jan Brett]. It’s about a little boy and his grandmother. She made mittens for him, and she said, “Don’t lose your mittens.” (He does lose a mitten, and forest animals use it for shelter.)

We actually created all of the animals in the story and recreated the story for the children. We want them to be able to do the beginning, the middle, and the end of a story. But we also wanted them to have basic skills like cutting paper and being able to do a sequence. And everybody had their own mittens.

We never thought they would enjoy it so much and talk about it throughout the week. Everyone was talking about gloves and mittens because everyone had them in the classroom.

What’s an object in your classroom you can’t live without?

My apron. I have children that give me things every single day, whether it’s toys, something they found, or something they want me to fix.

The children know that I always wear an apron. Some that people have created for me or that I’ve made for myself, or even the aprons that Starfish provides for us.

But it always has at least two or three pockets, and the pockets are always full of something. And children are always adding to that.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

I’ve always been a student. I enjoyed school. I felt like it was not only giving me different experiences but also giving me opportunities.

When I’m not working in the summer, I’m always learning something new.

I bring in some of the skill sets I learn to the classroom, whether it’s a musical instrument or things about how to stretch a story like the mitten, or ways to improve the space we’re in.

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.