James Rautiola, an Upper Peninsula superintendent, has lost a lot of sleep stressing about how he would get certified teachers to lead classrooms in the Copper Country Intermediate School District.

“We’re not the only industry suffering with trying to find employees, but we have a great opportunity in front of us to make it right for kids,” he told the Michigan Board of Education at a meeting Tuesday. “The time is right for us to explore some options.”

State superintendent Michael Rice has some ideas to mitigate the state’s teacher shortage. He presented them to the board Tuesday, saying it could take a state investment of $300 million to $500 million over the next five years to effectively address the problem. That’s a fraction of the $17.1 billion annually the state currently spends on schools.

“The fact of the matter is that this is a major issue across the state,” Rice said.

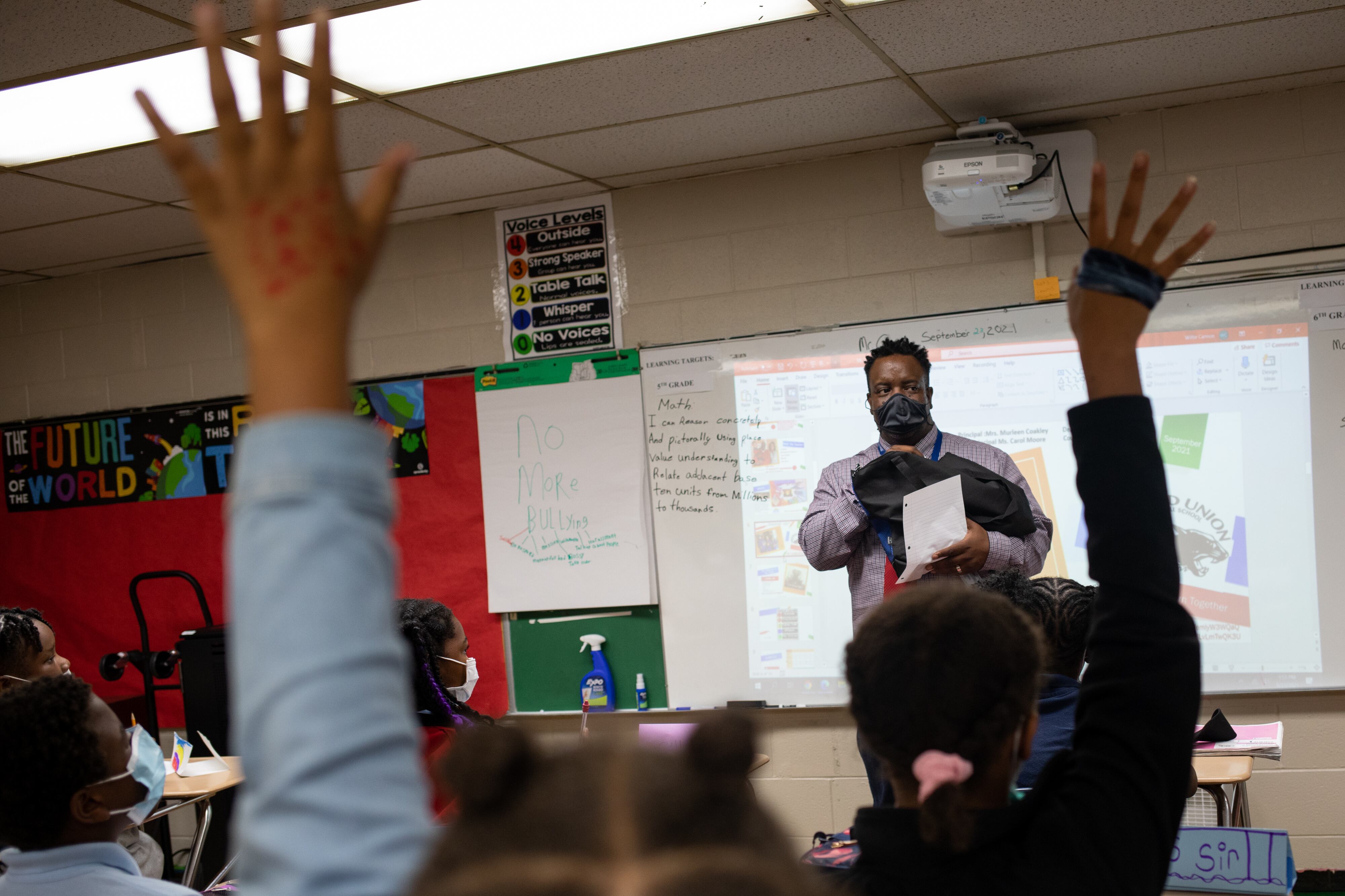

Numerous districts have temporarily closed schools or shifted them to remote learning because of teacher shortages exacerbated by faculty illnesses and quarantines.

And the problem isn’t just in Michigan.

Unprecedented teacher shortages throughout the country have resulted in students learning in larger classes, from teachers who aren’t always certified, or without the extra help districts had hoped to provide to help children catch up from last year’s learning losses.

Increasing teacher pay, especially for entry-level educators, is a major part of the solution, Rice said. Some beginning teachers in Michigan earn less than $40,000 a year, he said, and colleges have seen a large decline in students who want to enter the teaching profession.

“I’m going to keep beating this drum. We need to boost teacher compensation, and we need to particularly do it with early career teachers,” he said.

He offered the state board Tuesday a menu of other mitigation options, many of which would require legislative action and funding. They include:

- Offering tuition reimbursement for college students in education programs.

- Forgiving current teachers’ student loans.

- Awarding scholarships to promising high school seniors entering teacher training programs.

- Reviving teacher preparation programs in colleges in the Upper Peninsula and northern Lower Peninsula

- Easing restrictions on accepting teacher licenses from other states.

- Simplifying the employment pathway for people who graduated from teacher preparation programs but did not complete all requirements for certification.

- Expanding eligibility for child care reimbursement for students enrolled in teacher preparatory programs.

- Providing tuition reimbursement for teachers who complete reading courses required for a professional teaching certificate.

- Offering stipends to defray living costs during student teaching.

- Funding district efforts to recruit and retain teachers.

“We need to look at teacher supply. We need to look at quantity, quality, and diversity. They are all important,” Rice said.

He cautioned districts against relying too heavily on the recent infusion of federal COVID relief dollars because that money will run out in three years.

“We do have an opportunity with new funding but we have to be very, very careful with that funding,” he said. “You ought to be very, very careful not to put recurring expenditures on nonrecurring revenue.”

Existing “grow-your-own” programs that help members of school support staff become certified teachers are helping on all three fronts, Rice said. So are efforts to encourage high school students to enter the profession, he said.

Both the K-12 student population and the support staff ranks are more diverse than the state’s teaching pool.

“To actively inspire, interest, engage, and recruit from these two groups is to work not simply on quantity and quality, but also on diversity,” Rice said.

A number of factors contributed to increases in teacher vacancies during the pandemic. Some educators burned out from the increased pressure of moving between remote and in-person teaching. Others left because they were afraid of contracting COVID in their schools or because they didn’t want to comply with staff vaccination policies some states have adopted.

No matter the cause, the problem has left districts with more vacancies than ever.

Rice didn’t quantify the vacancies and Michigan Department of Education spokesperson Martin Ackley said the department doesn’t collect that data.

District administrators say they are filling the gaps by increasing class size, bringing in substitutes, shifting staff to classes they may not have the subject-matter expertise to teach, and hiring job candidates they might not have hired before.

The problem is urgent, said Michigan Teacher of the Year Leah Porter.

“The stakes have never been higher on teachers, and they feel that pressure. They are just burned out beyond belief,” said Porter, who teaches third grade at Wilcox Elementary School in Ingham County’s Holt School District. “If we’re not changing some of these things quickly, we’re going to continue to see teachers leaving the profession.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly reported the estimated cost of the proposed initiatives.