Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

At Lew Wallace School 107, principal Arthur Hinton sees students come from all over the world.

The sounds of Spanish, Swahili, Kinyarwanda, and Arabic can fill the halls of the K-6 school on the west side of Indianapolis, near the “international marketplace” neighborhood. In recent years, the school has attracted more students whose families hail from Haiti, speaking French or Creole.

Roughly 70% of the 509 students are classified as English language learners, a population that has only increased since Hinton arrived in 2020.

“Don’t blink again,” he joked. It might grow even more.

Lew Wallace is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse schools in the district. But its growing share of English language learners is emblematic of a trend that’s appearing across Indianapolis Public Schools.

More than a quarter of the district’s students are now classified as English language learners — over 6,700 as of late February, an increase of over 2,000 students since 2017-18. As in many other districts, staffing up for those levels has been a challenge. At the end of February, the district had eight vacancies for English as a New Language teachers, out of 110 positions total. Bilingual assistants can be even harder to come by: The district had 24 vacancies as of that date for its 76 positions.

Amid a larger push for equity in its Rebuilding Stronger reorganization, the district now plans to reimagine how it serves English language learners. Officials say instruction for these students should be more consistent across school buildings, and allow students to learn alongside their native English-speaking peers. Students learning English, they say, should not be restricted from classes such as music or art because they are pulled away for separate English language learner instruction.

The plan includes assigning each school at least one leading English as a New Language “teacher of record,” responsible for overseeing the school’s English language learner program. It also involves more incentives for staff — including a $2,000 stipend for lead teachers and reimbursement for some English as a New Language teachers who also train to become certified to teach English language arts.

The plan is one of the district’s budget priorities for the 2024-25 school year.

“It’s going to be hard, without a doubt,” said Arturo Rodriguez, the district’s director for English as a New Language. “We’re up to the challenge.”

IPS plan encourages more co-teaching, less separation

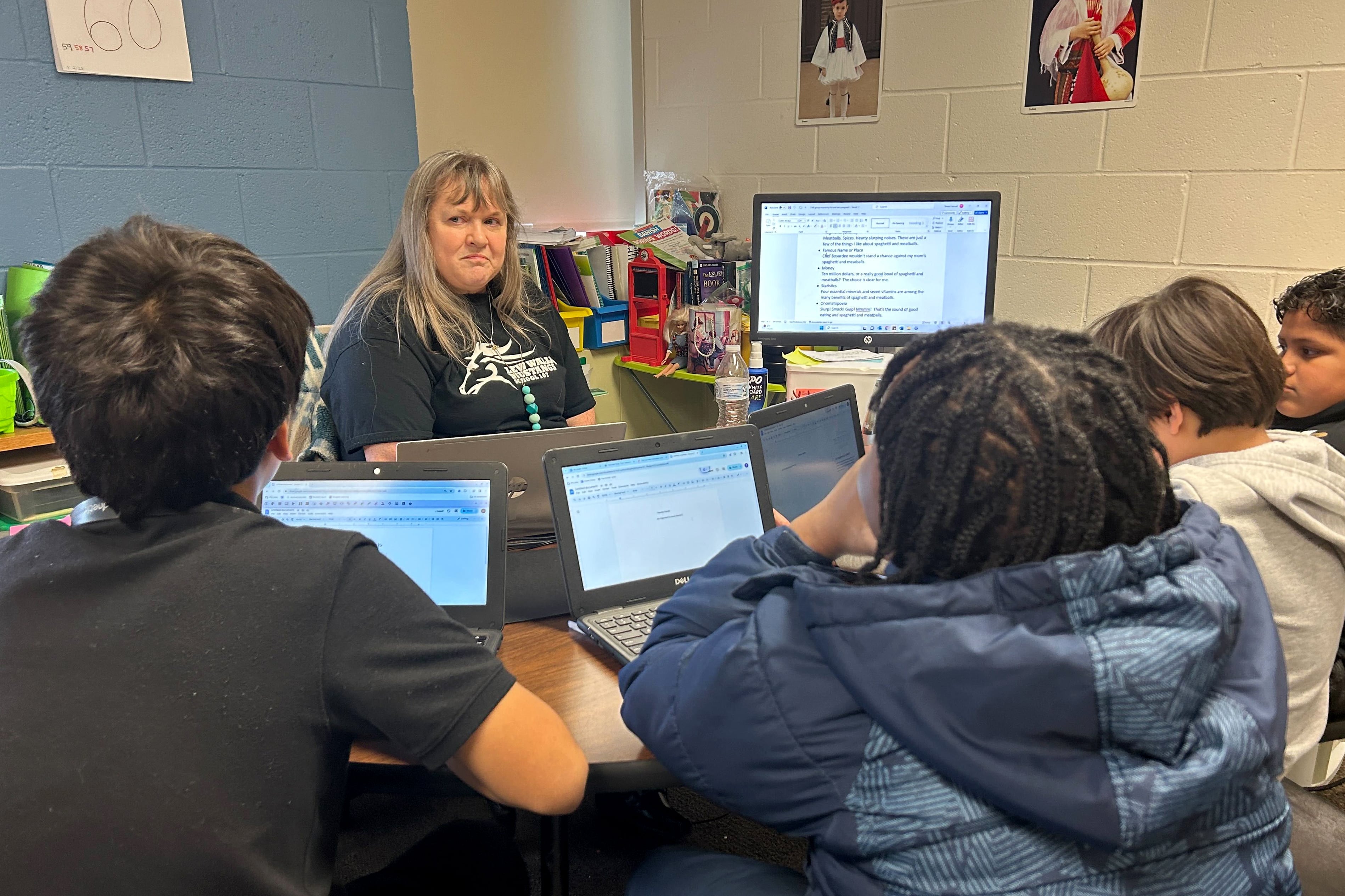

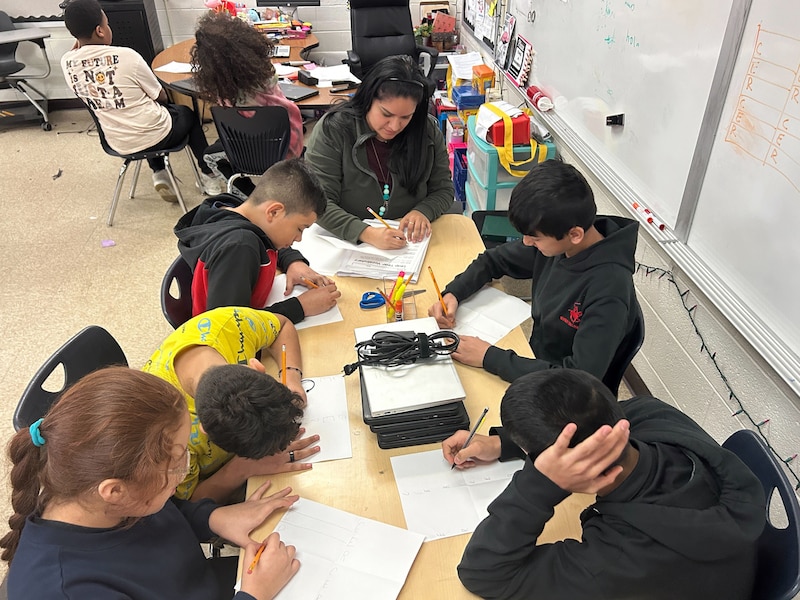

In a sixth grade classroom at Lew Wallace, Ana Gonzalez sits with a small group of six students, alternating between Spanish and English as she teaches the concept of claims, evidence, and reasoning in language arts.

Just a few feet away, the main classroom teacher is reviewing the same topics with the other students. At Gonzalez’s table, though, the focus is on the English learners.

“You guys in class have been working on claims — finding a claim and finding evidence,” Gonzalez tells her students. “Tener, como, un reclamo y evidencia.”

The school uses a form of co-teaching, where English language learners are in the same classroom as their native-speaking peers, and learning the same things at the same time.

This is the type of model that the district hopes all schools will embrace.

Right now, instruction for English language learners varies from school to school. Only some IPS elementary schools offer co-teaching, while others don’t have enough staff. Sometimes teachers are used as interventionists — staff who pull students away from class to work directly with them on their specific needs — rather than as co-teachers.

At the middle and high school levels, some English language learners do not have access to electives, because their English as a new language instruction is held during those times.

The district’s plans would mean less separation, and more exposure to the mainstream classroom as students learn English.

The philosophy: Everyone is an English as a New Language teacher.

An English as a New Language teacher “is supposed to help support language development, not necessarily spending their whole day doing intervention,” Rodriguez said. “There are some places where more than 80% of the day, that’s all they’re doing.”

At each school, a lead teacher of record will be responsible for the battery of tests that English language learner students must take to ensure that they pass the language proficiency test known as WIDA ACCESS.

That will free up the school’s other English as a New Language teachers to teach more throughout the day, Rodriguez said.

Rodriguez is also hoping those lead teachers will monitor proficiency on state exams for English learners, which dropped after the pandemic, as it did for other student subgroups.

Last year, 47.9% of these students passed the third-grade IREAD exam, while 3.2% reached proficiency on both English and math sections on the ILEARN in grades 3-8, according to state data. (The figures do not include charter schools in the district’s autonomous Innovation Network.)

The district hopes to train English as a New Language teachers and main classroom teachers on the new changes.

Staffing poses a challenge

At Lew Wallace, Hinton acknowledges that he’s blessed to have five English as a New Language teachers. The school also has four bilingual assistants speaking Spanish and Arabic.

But at other schools in the district, filling those roles may be more challenging.

As of early March, the district anticipated the need to fill about one dozen English as a New Language teaching positions for the next school year.

Bilingual assistants, Rodriguez said, are particularly difficult to find amid stiff competition among districts. The district urgently needs candidates who speak Swahili, Kinyarwanda, French, and Haitian Creole, he said.

IPS hopes a few initiatives can help with the staffing needs.

The district is beginning to reach out to local universities to build a pipeline of bilingual assistants who can eventually transition into certified teaching positions, Rodriguez said.

The latest contract with the teacher’s union approved in November also offers base-pay increases for English as a New Language teachers and other in-demand positions.

And IPS also plans to offer English as a New Language teachers in middle and high school incentives to become dually certified to teach English language arts. That could reduce the number of staff needed to teach both topics.

The district would reimburse teachers for the cost of taking the Praxis certification exam for English language arts, which is over $100.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Lawrence Township schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.