Sign up for our free monthly newsletter Beyond High School to get the latest news about college and career paths for Colorado’s high school grads.

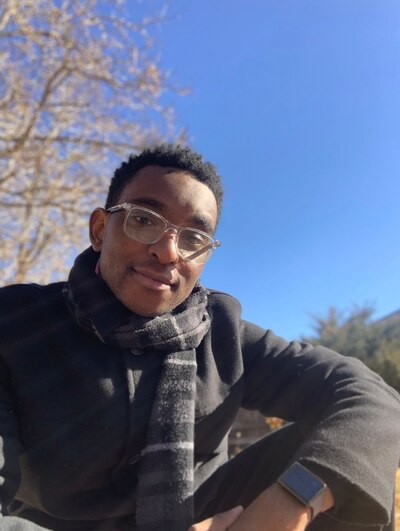

Two years into college during the pandemic, Larry Blackshear wanted a little bit of normalcy.

Hoping a move closer to home would help, he decided to transfer in 2022 from Colorado State University Pueblo to the University of Colorado Denver — a 15-minute drive from where he grew up in Aurora.

But even though he wanted to pursue the same Spanish and political science degrees he studied in Pueblo, not all of his credits transferred with him. Of the 82 credits he had earned, only 64 were accepted at the Denver university.

“If CU Denver had accepted my credits,” Blackshear, 23, said, “I’d be preparing to graduate at the end of this (school) year.”

Instead, he’s likely a year and a half away from earning his degree. And, while he’s not sure of the exact amount, he estimates he’s spent thousands of dollars trying to catch up.

Colorado was a pioneer in working to remove such obstacles with transfers, but students statewide still run into problems when they try to switch between public colleges, pointing to the need to update rules to reflect changes in the way students earn credits and progress through college.

State leaders hope new legislation will provide that update, so that students like Blackshear don’t lose time, money, and credits when they decide to change schools.

Senate Bill 164 includes three different parts to bolster the state’s transfer system. The bill is a priority of the Colorado Department of Higher Education and is sponsored by a bipartisan group of lawmakers.

The bill would update the state’s student bill of rights — a list that says what students can expect from colleges — for the first time since 2008. The updates would include a requirement that schools tell students whether their credits transfer and what a transfer to another school entails. They would also have to clarify that students have the right to appeal if an institution decides their credits won’t transfer, and the legislation lays out a process for an appeal.

The bill would require colleges to give students information about college costs, including fees and other expenses.

And the bill would require a state report on transfer outcomes, such as how many students transfer statewide and how transfer credits were applied by colleges toward a student’s transcript.

Colorado’s pioneering transfer policies falling short

Colorado was an early adopter of common course numbering, which standardizes certain class numbers across colleges and universities, so that they’re more easily recognized by the receiving college and the credits transfer seamlessly. The state also has other policies for transfer students, such as agreements between two-year and four-year colleges and universities that help students stay on track to earning a degree.

But not all Colorado colleges have such agreements, especially when students transfer between four-year universities. And the system hasn’t evolved fast enough to keep up with changes over the past decade, said Kim Poast, the Colorado higher education department’s chief student success and academic affairs officer.

More students are taking college courses in high school, and the state has more workforce training programs that teach college-level skills. State leaders have also recognized that students move between colleges and universities in ways not accounted for within the current system, which is built around the idea that most students would move from community college to a four-year university. Students take much more winding paths than that and can end up attending multiple universities before they graduate, Poast said.

Statewide groups have also taken notice of issues with the state’s transfer system, especially as national data has shown more than a third of all students transfer. Colorado’s The Attainment Network recently released policy suggestions for the state to update its transfer policies, such as ensuring certain credits transfer into programs and collecting data on how the system works.

Poast said the state worked with two national organizations to create recommendations for updates, some of which are reflected in the new legislation.

The goal of Senate Bill 164 is to help more students when they run into issues and identify and fix where schools are running into issues applying transfer credits, Poast said.

“I think it’s so important for students to have agency and be able to see how to navigate that system in the most effective way possible,” she said.

Barriers cost students time and money

Katherine Harvey’s experience typifies the challenges the new legislation seeks to address.

Harvey, now 27, graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder in 2019. But she took a winding route. She started college in California, then transferred to Front Range Community College. She had some credit from Advanced Placement courses in high school, but her California credits didn’t transfer properly.

She ended up having to retake a math class, because her California math class counted for only 2.7 credits. She needed three to meet graduation requirements.

When she eventually transferred to CU Boulder, the school again needed to independently review all of her transcripts, including the credits she earned from Front Range. This time, she kept a detailed record that she gave to advisers.

“Even though that was like all within Colorado, it was so confusing, and I never really got guidance,” she said. “And then you’re paying extra money, and you’re a poor college student.”

The bill is expected to be heard in committee for the first time on March 20. It has support from colleges and advocacy groups statewide, although several are asking for changes.

Katie Zaback, Colorado Succeeds’ vice president of policy, said the bill is a step in the right direction. But her organization wants to see a requirement that the state publicly report information, such as the challenges schools encounter with accepting credits and how the state is responding to those issues. Colorado Succeeds brings together business leaders to advocate for improving education and training.

For Blackshear, the changes can’t come fast enough. He’s not sure when he will graduate. And financial aid he once relied on has run dry, meaning he has to find more money for college.

He plans to testify in support of the bill, because he doesn’t want other students to run into the same issues he has faced. He hopes his testimony can show that the transfer system needs updates to help students who are falling through the cracks, most of whom are students of color and the first in their family to go to college, he said.

“I hope that my story is able to alert students about the challenges and perils of transferring from institution to institution without having all of the knowledge that they need to be successful,” he said. “And I hope it can show just how detrimental the transfer processes are.”

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage. Contact Jason at jgonzales@chalkbeat.org.