This story was reported in partnership with Open Campus.

Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter Beyond High School to get the latest news about college and career paths for Colorado’s high school grads.

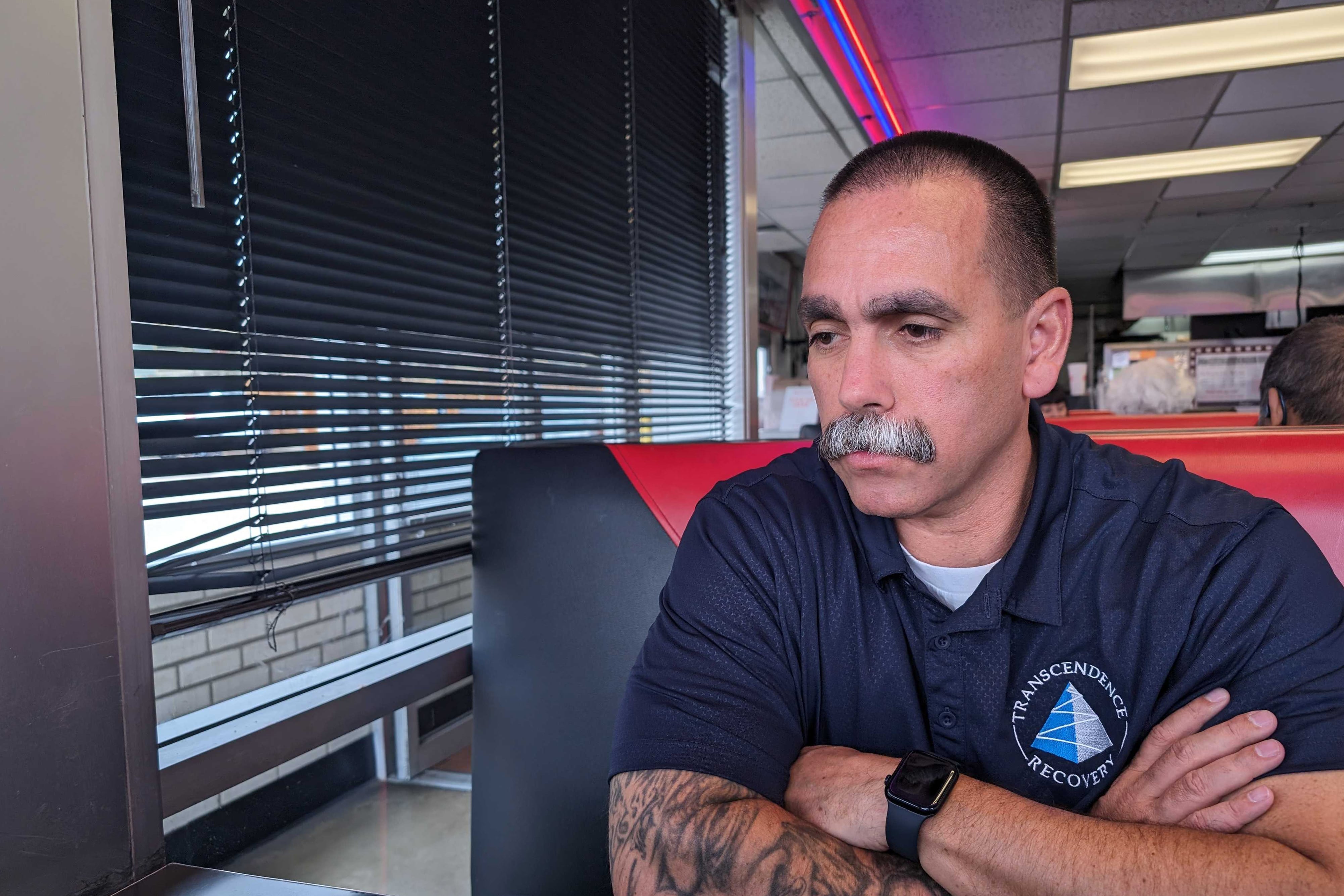

David Carrillo often envisioned himself walking into a diner just like Jim’s Burger Haven in Thornton. Or maybe browsing in Walmart or some other store.

He had heard so many stories about others out on parole getting overwhelmed in new situations, especially after almost three decades in prison. He wanted to be prepared for his release at the end of January from the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility.

“I would kind of visualize myself walking through these different areas and being OK,” he said during an interview last week.

So far, as he’s transitioned into his new life, there have been very few moments where he’s felt uncomfortable, Carrillo said after eating Jim’s classic smash burger and fries. Sure, he has had to figure out his style — he really likes Levi’s — and the grocery brands he likes to eat and favorite restaurants.

But Carrillo, 49, has eased into exactly what he said he wanted to do before his release — continuing to teach and “pay it forward.”

After becoming one of the first incarcerated professors in the country to teach other incarcerated students, Carrilllo was released after Colorado Gov. Jared Polis granted him clemency in part due to his work as an Adams State University educator. Carrillo got back to the classroom just a week out of prison.

He works at Transcendence Recovery, a substance recovery center started by a colleague Carrillo served time with, where he said he gets to work with people struggling with addiction and help them “lift themselves up whenever they’re ready.”

He also works part-time at Red Rocks Community College assisting with the adult basic education certificate program the college is offering to students in prison. And this summer, he’ll rejoin Adams State as an adjunct professor teaching incarcerated students.

This time, though, he isn’t wearing the same green uniform as his students.

“I’m just hopeful that something great happens for all the people that I know and don’t know so they can get an opportunity to find another chance at life,” he said.

At the beginning of April, Chalkbeat Colorado and Open Campus caught up with Carrillo after his exit from prison. Here’s what he had to say about his reentry, goals as a teacher, and how he views his story:

‘A lot of discovery’ since he was released from prison

Carrillo had gone through the shock of a changing world once before. When he was younger and got out of juvenile detention as a teenager in the 1990s, he remembers getting overwhelmed by everything that changed after a year.

“Everything seemed so weird and strange to me,” he said.

This time, even after almost 30 years, the biggest shock was that he wasn’t as shocked by life on the outside.

He’s had at least one moment where he felt uncomfortable since his release. In a diner in Florence on the day he got out, he met with family and friends for breakfast. He ate with silverware and not a plastic spork for the first time in decades. He doesn’t even remember what he ordered because it was so amazing to be eating with his sister, but he said he felt anxiety creep up when a group of prison guards from the nearby federal penitentiary walked in to eat too.

He said his sister noticed a change in his mood. They wrapped up the meal and left.

Moments like that are rare, he said. Still, he has needed to navigate shopping for himself, although his sister offers her advice. He didn’t have a style, he said, because he wore a green prison uniform for almost his entire life. He also sought out healthier food than what he ate on the inside.

He also said he has to remember that he can use Google to get immediate answers to his questions rather than having to ask a friend or family member to look something up for him.

“There’s a lot of discovery going on,” Carrillo said.

Work as an educator continues to be a big part of his life

Through Transcendence Recovery, Carrillo is learning how the business operates and has earned a certification to be a recovery coach that allows him to work directly with clients, he said.

In his part-time work with Red Rocks, he’s assisting faculty with an adult basic education certificate program. About 20 incarcerated students in the Colorado Department of Corrections are currently earning the certificate, which will allow them to work as GED tutors and peer mentors inside.

Carrillo said he’s excited to be part of an initiative that increases access to education for those inside: “It feels awesome to be able to Zoom back in on Fridays to help teach the program and to let everybody see me.”

The adult education certificate program is partially a response to staffing shortages within the corrections department. GED staff also have to act as guards, which takes time away from teaching.

Training incarcerated people as educators helps ensure that interruptions don’t derail incarcerated student’s education.

“Motivation is a hard thing to maintain inside,” he said. “And so when programs stop for an extended period of time, it’s kind of hard to maintain any kind of consistency and any motivation.”

He’s also excited to be part of the Adams State program in the summer. He will be teaching incarcerated students live on Zoom as well as working with students in the university’s print-based correspondence program.

He can relate to his students’ struggles

Students trying to learn in prison face numerous challenges, and Carrillo knows exactly what they are going through.

One of the ways he has prioritized helping students during Zoom is by ensuring they get as much feedback as he can possibly provide them. He hasn’t gone back in since he was released. He enjoys being able to connect with his former students and others virtually, but he wishes they were out too.

Communication with people on the outside can be difficult, he said, and when he was completing his MBA through correspondence courses, most professors were willing to answer questions. But sometimes it would take a long time to communicate over snail mail.

“I hope to be able to answer my students as promptly as possible,” he said. “I want to give them a better opportunity to have timely information for their tests and everything like that.”

Teaching has opened up doors

Carrillo said that he started making better choices 15 years ago when he decided he wanted to take a different path. Those choices helped him build both a professional and personal network, including with corrections staff members.

“All of this stuff, the education and other programs, has allowed me to walk out here and find a job. I still have a multitude of opportunities that if one happens to fall through,” Carrillo said. “Education on the inside, it also opened up more doors than just job opportunities.”

He’s been invited to speak at a conference in Washington D.C. this summer. That’s also a first – it’ll be his first trip since he was released.

“That wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for the education that I did, and then becoming the first adjunct professor inside of DOC (the Colorado Department of Corrections.)”

His peers cheered when they heard he received clemency

He’s not sure just how much educating himself weighed into the decision, but it did help him change.

Carrillo said he was young when he went to prison. He didn’t have much of an education. Over the years, as he decided to dedicate himself to learning, he grew as a person. He never actually expected his release to happen even as he prepared himself for the possibility.

His incarcerated peers cheered when they heard the news about his clemency.

“They were happy for me, but for themselves, they saw that there’s opportunity here,” he said. “If that can happen for somebody with my background, what’s possible for them?”

Education changed the way Carrillo saw the world and the world saw him

In 1994, at the age of 20, Carrillo was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. While having a felony conviction generally shuts doors, it was inside that Carrillo said he found opportunity through education.

“Here’s an individual who was your stereotypical DOC inmate who should have spent the rest of his life in the penitentiary. If you knew my story from day one, I was that guy,” he said. “And, man, look at what happened after I decided to do that complete 180 with the way I saw the world and with the way the world saw me. It’s awesome. I guess that’s the story, right?”

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage. Contact Jason at jgonzales@chalkbeat.org.

Charlotte West is a reporter covering the future of postsecondary education in prison for Open Campus. Contact Charlotte at charlotte@opencampusmedia.org and subscribe to her newsletter, College Inside.