People incarcerated for nonviolent offenses in Colorado could earn time off their sentence if they get a college degree or credential.

Supporters of House Bill 1037, which the House Judiciary Committee approved 11-2, say it will help incarcerated Coloradans find new opportunities and make it less likely they reoffend after release while also saving the state money.

The bill would provide incentives to state prisoners to take advantage of federal grants available to them starting this summer. The federal government also has expanded how many colleges and universities can educate incarcerated students, opening the door for more opportunities.

State Rep. Matthew Martinez, a Monte Vista Democrat sponsoring the bill, said to the Judiciary Committee that financial assistance removes the biggest barrier facing imprisoned students wanting to go to college.

“We’re getting them back on track and really making a difference in changing their lives,” said Martinez, who previously ran Adams State University’s prison education program. State Sen. Julie Gonzales, a Denver Democrat, is also sponsoring the bill.

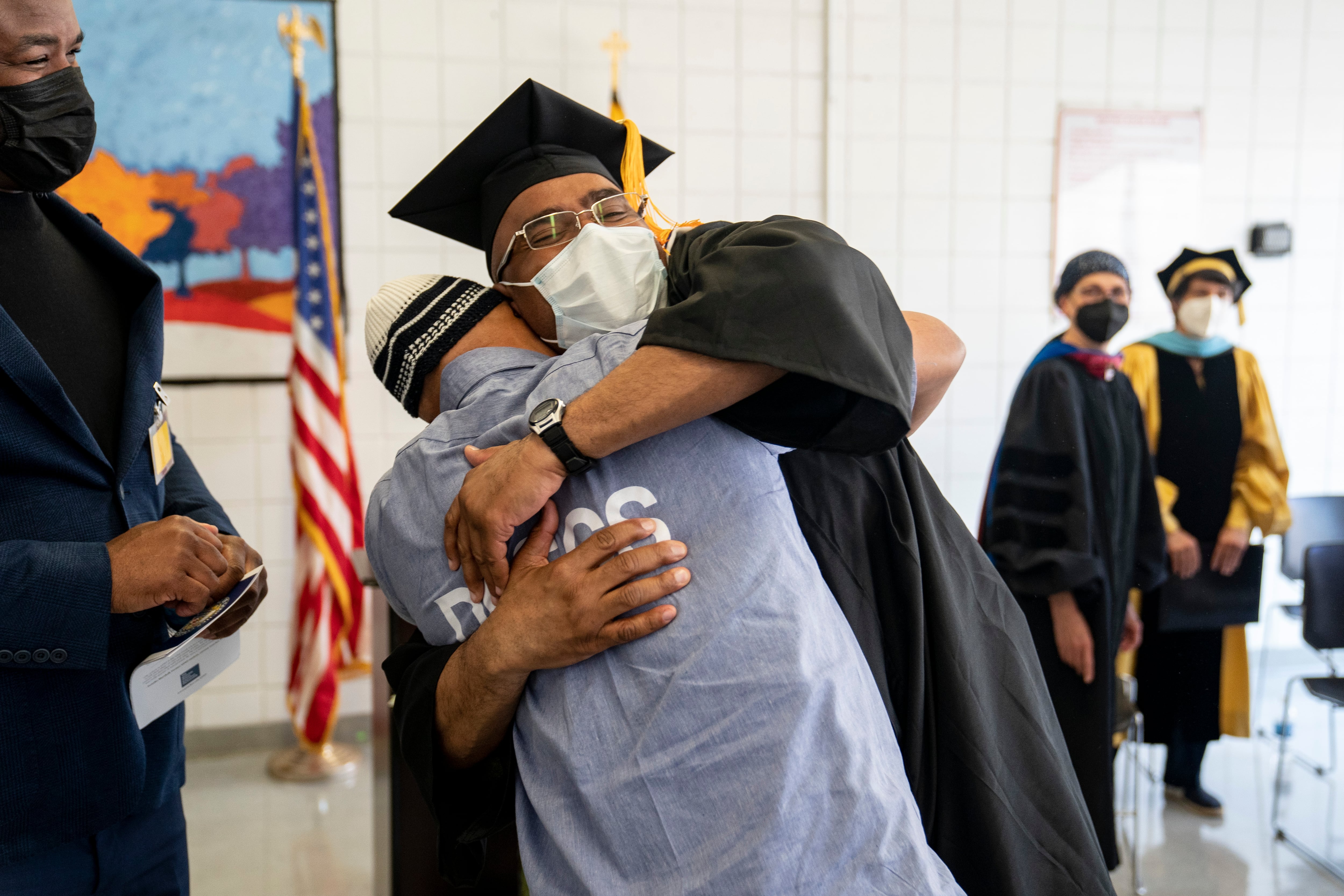

Bikram Mishra, who testified to the committee, said that during his 10 years in a Colorado correctional facility his family helped pay for his college classes. It changed his life, he said, and he wants college access for other people in prison.

“We are trying to help people get better and we are trying to make sure that they’re ready for society,” Mishra said.

If signed into law, Colorado would allow students convicted of nonviolent offenses to earn six months off their prison sentence if they earn a college credential or certificate. It would also allow them a year off their sentence if they graduate with an associate, bachelor’s, or master’s degree.

Some Republican and Democratic lawmakers, however, advocated during the hearing for increasing the amount of time incarcerated students would earn for an early release. Some worried that a year off their sentence would not be enough to attract students to degree programs and they would instead seek out short-term programs.

The bill would split money the state saves by releasing incarcerated students early between higher education institutions and the Colorado Department of Corrections.

Republican state Reps. Matt Soper of Delta and Stephanie Luck of Penrose voted against the bill in part because they want the Colorado Department of Corrections to keep more of the savings.

But all committee members, even those who wanted to see changes, said they support the idea to encourage people in prison to get an education. They said the testimony of former prisoners-turned-college graduates moved them to support the bill.

Martinez said data shows graduates are less likely to reoffend, especially if they earn a bachelor’s or master’s degree. That also means less cost to society, he said. In 2018, Colorado had one of the worst recidivism rates in the country — half of all formerly incarcerated people returned to prison within three years. National studies, however, show incarcerated people are less likely to reoffend if they get access to education.

Christie Donner, Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition executive director, said allowing incarcerated people the ability to learn while in prison goes beyond just what it saves the state. The bill represents the start of more conversations to ensure incarcerated people see a future for themselves, she said.

“Education helps you see yourself differently,” Donner said, “You have different ambitions and hopes and dreams and all that kind of good stuff. It’s really profound. And it’s so much better than just going to make license plates or sweep the floor or work in the kitchen. People can find a whole new life.”

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage. Contact Jason at jgonzales@chalkbeat.org.