Erin Schneiderman used to get calls in the middle of the day two or three times a week to pick her son up from his Denver elementary school.

The third-grader had run away or was standing in the hallway screaming. Meltdowns could last for hours. School was just too loud and crowded, with too much unpredictability, for a child with autism who craved routine.

Denver Public Schools decided Schneiderman’s son should go to a privately run school that specializes in serving children with intense behavioral, mental health or special education needs. But when it came time to start fourth grade, he still didn’t have a spot. The boy spent two months at home, most of that time getting no education at all.

Today, nearly five years later, the few options for Colorado students like Schneiderman’s son have dwindled further. In 2004, Colorado had 80 of these specialized programs known as facility schools. Now there are just 30 that serve an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 children a year. A single school serves all of western Colorado. On the Front Range, another school is set to close soon.

Meager state funding, dire staffing shortages, and changes to federal law have pushed the system to the brink. Lawmakers hope a cash infusion and regulatory changes will spur the opening of new schools — even as school districts are seeking their own solutions.

When there’s no open facility school seat, children may languish at home. They may remain in a mental health facility longer than they need to, taking up a bed that could be used by another child stuck in a hospital emergency room. Or they may stay in classrooms, struggling to learn, coming undone, lashing out almost daily, and disrupting the learning of their classmates.

Parents pay the price in lost jobs, and children pay the price in squandered potential.

Public schools have an obligation to educate every child. Facility schools — which operate at the crosscurrents of education, mental health, disability, and trauma — serve as placements of last resort when public schools can’t or won’t meet a child’s needs.

“K-12 was set up to educate the masses,” said Cori Woessner, a career public school educator who isn’t sure her own son with disabilities would have finished high school without the more supportive environment provided in facility schools.

“We’re not talking about the masses. We’re talking about the kids with the most severe needs that need the most support to be a productive member of society. To even have a chance at it.”

Facility schools balance academics and therapy

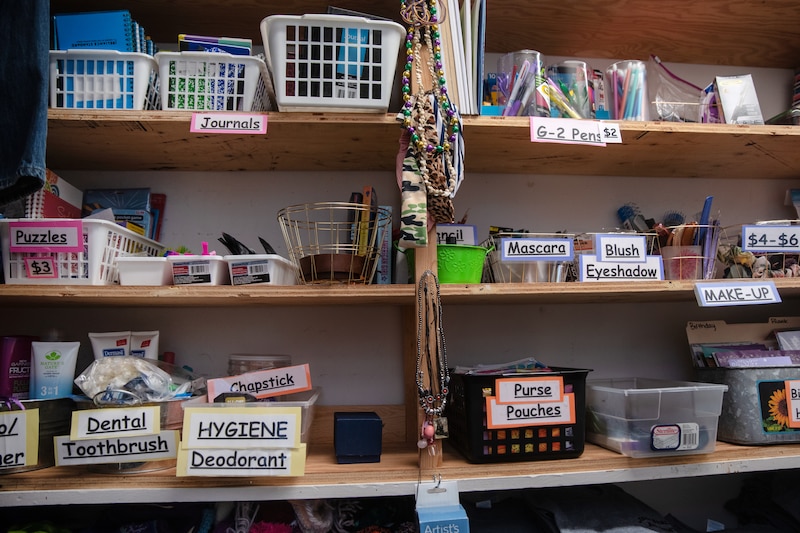

Facility schools are neither mental health facilities nor schools in the way most people might think about them. Operating in day treatment centers or residential facilities or tucked into hospitals, they offer academic programs within larger therapeutic settings.

Some critics say facility schools too often end up warehousing kids who, with more support, could have stayed in their home schools. Oversight is spread across multiple state and local agencies. When a school district recommends a facility school, parents have no easy way to know if the school is good or safe, though they rarely get a choice about placement.

The goal is to help children stay on an academic path while developing the skills they need to function in a public school before sending them back.

Some facilities serve children in foster care who need mental health care, or children in the juvenile criminal system who need treatment before returning home. The more common scenario is that students live at home and school districts send them to day treatment programs.

“Once we make that decision, it’s not because we don’t like kids and we’re sending them somewhere else,” said Callan Ware, the executive director of student services in Englewood Schools, a small district south of Denver. “We are saying we like them so much, we care about them so much — and we’re admitting to you we don’t have what it takes to support them and we’re going to find it and we’re going to pay for it.”

The Tennyson Center for Children is a facility school located in a bright, modern building in a residential Denver neighborhood. It serves about 50 metro-area students in kindergarten through 12th grade. The staff seems to have endless patience for behavior that would likely get a student kicked out of public school.

On a recent Friday, a middle schooler raged in a stairwell and called the principal a “fucko” because the school removed the game platform Roblox from its computers.

A high schooler who couldn’t sit still tossed a foam basketball at a staff member’s face as she drank from a water bottle, soaking her shirt.

And an elementary student ran up and down the hallway letting out a series of screams between his spelling words and math problems.

The boy was working with a staff member in one of the “nooks” — a small recessed room without a door where students can retreat if they’re feeling overwhelmed.

“I don’t want to do any more work!” the boy said, coming out of the nook and kicking the wall.

“To earn our positive breaks with staff, we have to complete work,” the staff member said, reminding the boy that he was working toward earning computer time in the library.

“It’s hard for me,” the boy said. He asked why his classmates, who had just completed a worksheet on Presidents Day, were earning points for good behavior and he wasn’t.

“Because they stay in class,” the staff member calmly told him as he pouted and fumed. “Part of the expectation of being in school is staying in class.”

The boy went back into the nook and screamed again.

When funding dries up, kids are funneled down

Children with these challenges were once institutionalized.

“Almost every general hospital had a kids’ psych unit, and they were all full,” said Skip Barber, a retired child psychiatrist who worked at state mental health institutions and facility schools.

The psychiatric facilities created their own schools. But since the 1990s, the philosophy has shifted away from institutionalization and toward community-based care. Residential treatment programs began receiving kids in crisis who previously would have gone to hospitals. Day treatment programs took kids who would have been placed in residential facilities.

And more kids just stayed in public schools.

The Medicaid dollars that supported the previous system dried up. Twenty residential treatment facilities closed in Colorado between 2007 and 2017, according to newspaper reports. On the heels of those closures, Congress passed the Family First Prevention Services Act, which sought to keep more children with relatives or foster families and placed limits on government-funded residential care.

More residential programs closed, taking their associated facility schools with them or reducing capacity. Options in rural Colorado — where the nearest school might be hours from home — became even scarcer.

“Great if we move away from facilities that aren’t cutting the mustard or doing what we need, but now we’ve gone too far,” said Becky Miller Updike, executive director of the nonprofit Colorado Association of Family and Children’s Agencies, which represents residential facilities.

More children in crisis are now funneled into day treatment programs. But the funding hasn’t increased in tandem.

In a 2020 survey, administrators at 19 facility schools told Miller Updike they were nearly or solidly in the red. One reported having to fundraise $1 million a year.

“The program loses money on a regular basis,” another wrote.

Most funding comes directly or indirectly from the state. Facility schools get $55.05 per student per day in direct state funding, an amount that’s barely increased in the last eight years, said Judy Stirman, director of facility schools for the Colorado Department of Education.

School districts pay tuition fees on top of that, ranging from $75 to $348 per day. Students come and go throughout the year, which means the daily funding comes and goes. But the salaries of the experienced specialists and one-on-one aides who make the system work are constant.

Low funding means it’s hard to hire staff. Facility schools often pay their staff less than school districts, which struggle to fill the same positions. That limits how many students they can serve.

“Every hire, we can bring in a student,” said Amy Gearhard, founder of Spectra School, which started as a therapy clinic for children with autism. Most students need one-on-one aides.

But the job is hard, and new hires don’t always stay. The aides at Spectra take 40 hours of behavior technician training and often wear bite guards and spit shields.

Despite those precautions, Gearhard said in January that three Spectra staff members had suffered concussions on the job, and two were out on workers’ compensation claims.

“You can’t pay them $15 an hour,” she said.

Two longtime facilities that closed last year — the Hampden Youth Campus in Aurora, which ran three day treatment programs, and the Youth Recovery Center at Valley View Hospital in Glenwood Springs — cited low funding and staffing shortages.

“Last year this program lost over $300,000, which made it very difficult to be able to hire enough staff to work with the level of acuity that we were seeing in the students,” Aurora Mental Health Center Chief Clinical Officer Kirsten Anderson told the Sentinel Colorado.

Officials with Devereux Cleo Wallace, a day treatment program in Westminster that’s set to close this year, said in a statement that “the continued regional staffing shortages have made it no longer possible to operate our flagship programs at the levels our families deserve.”

But the staff who stay at facility schools say they’re drawn to working with this student population. Renée Johnson, executive director of Third Way Center, a residential facility that serves kids in foster care or youth corrections, said these kids are “used to being thrown away.”

“These alternative schools give kids chances to do it again and be successful,” Johnson said. “That feeling of success is so important to build on.”

Fewer schools means longer waitlists

Colorado is not alone in its hiring struggles. A nationwide shortage of special education staff means it’s harder for schools to provide the consistent support that would help kids with severe needs be successful in their home schools. At the same time, the inability to hire and retain staff has caused specialized schools nationwide to close or reduce their capacity, leading to students with disabilities being put on long waitlists, according to an October letter to Congress from the National Association of Private Special Education Centers.

“We’re seeing a supply and demand crisis on a national level,” said Danielle Damm, the association’s executive director and CEO.

In Colorado, the number of students served by facility schools has decreased. Thousands of students come and go throughout the year, but there are only so many spots at one time. A statewide snapshot taken on Dec. 1 each year found 1,266 students in facility schools in late 2017 but just 769 students in these schools in 2022. That’s a 40% decrease.

It’s not because the demand has decreased.

“We’re all on waiting lists because the facilities can only accept so many students and they’re short-staffed as well,” said Courtney Leyba, senior manager of extended school support for Denver Public Schools.

In Jeffco Public Schools, the number of students in out-of-district placements dropped 35% — from 211 students six years ago to 138 students this school year. In Denver, it went from 254 to 119 students in the same time period, a whopping 53% decrease.

Fifteen years ago, when Leyba started working for the Denver district, she said students would wait just two or three weeks to get into a facility school. “Now we can wait anywhere between two, three, or sometimes even six months for a placement,” she said.

In the wait, students can unravel even more.

Until he got into a facility school two months into his fourth grade year, Schneiderman’s son would have meltdowns over literally anything, she said.

She and her husband struggled to cobble together care for him. Grandparents from both sides of the family flew in to help, but Schneiderman ended up having to take a leave from her job. An in-home tutor the district promised didn’t start working with him until he’d already been home more than a month.

“It felt like we were completely lost in a system that we had no idea how to navigate,” Schneiderman said. “That had to have been one of the worst periods of our lives for sure.”

‘Effective in some cases, but not in all’

Many advocates and experts say students belong in their own communities, not separate schools that may be hours — or even states — away from home.

“Students don’t need to be segregated in order to have their needs met and be successful in school,” said Lewis Bossing, senior staff attorney with the Washington, D.C.-based Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. “We think that there are a number of different kinds of supports that can be put in place so that, for the most part, students can be served in general education settings.”

Advocates like Connie McKenzie with The Arc Pikes Peak Region worry about a lack of oversight, and about students getting stuck and never returning to public school.

One student McKenzie worked with attended a facility school from kindergarten through 12th grade. Another was a kindergartener who was referred to a facility school because the child kept running out of the classroom, she said. The child had gone through a traumatic event.

“Removing the child from the school, sending them to a different school, just reinforced to the child that they weren’t safe at school,” McKenzie said.

Facility schools, she said, “are effective in some cases, but not in all.”

People who work in the system say the typical stay is about a year, though it varies widely based on the facility and whom it serves — from less than a week for acute psychiatric hospitalizations to years at schools for students with intellectual disabilities.

The state education department doesn’t track how many facility school students return to their home districts or how they fare later.

But even critics acknowledge there are times when a separate setting is justified.

Zoe Gross, director of advocacy for the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, said that while inclusion is ideal, “if your school district just refuses, or is unable to meet the needs of your kid, then you have really limited options outside of that.”

That’s how Woessner, the career educator whose son attended facility schools, feels.

Her son, now 18, was first referred to a facility school when he was 8. Woessner and her husband adopted him out of foster care as a baby, and he has several diagnoses, including fetal alcohol syndrome, which affects his cognitive ability.

He couldn’t read or write his name in second grade. At 7, he made a plan to kill himself by running out into the street. At 8, he put a belt around his neck at school.

“We were very fortunate that happened when he was 8 and there were still 70-some-odd facility schools and they popped him into a facility school because of the severity of his behaviors,” Woessner said.

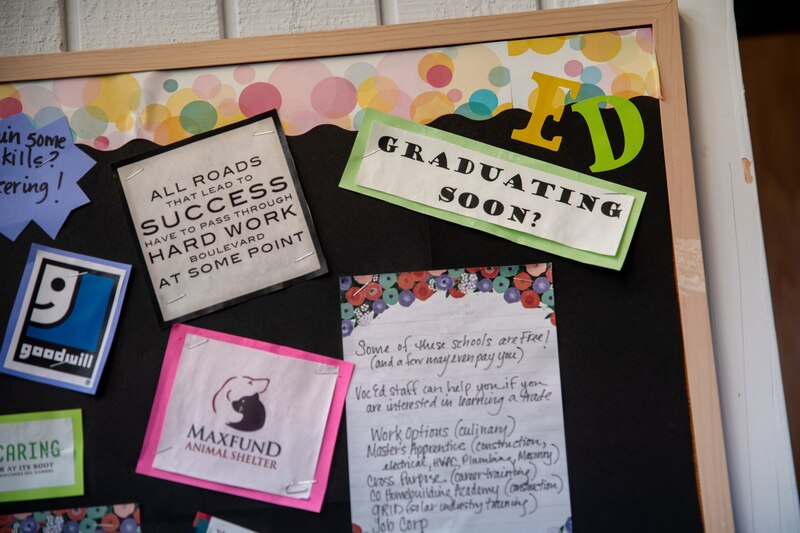

Her son spent the next 10 years in six different day treatment and residential programs, including one out of state. He completed 12th grade at a Denver facility school and is now in a small transitional program for older students with disabilities through his home school district.

“He made it a lot further academically going through facility schools than he ever would have in a traditional school,” Woessner said.

Moving ahead toward an uncertain future

A state law signed by Gov. Jared Polis this spring boosts funding for facility schools and revamps the funding model so small schools are less vulnerable to fluctuations in enrollment.

A new technical assistance center will provide consulting services and training in rural districts so that more students could stay close to home. And a new way of approving new schools should make them easier to open.

In advocating for changes to the law, the working group described facility school students as some of Colorado’s “most vulnerable.” Parents, advocates, and special education experts all say that meeting the needs of these children will require more than just saving the schools, however: Families need more options all along the spectrum of inclusion and separation, and children need more care as they make precarious transitions from one setting to another.

Schneiderman’s son did so well at Tennyson Center in Denver that everyone agreed he should go to public middle school, she said. He enrolled at Denver’s Merrill Middle School. But even in a small program with a dedicated teacher and a classroom where he could go when things got overwhelming, going to school with 600 other students proved tough.

Wanting to fit in, Schneiderman’s son rejected help from an aide in traditional classes. He got into fights because he misunderstood regular kid banter as bullying. His meltdowns — which can turn violent and have landed him in the hospital — returned both at home and at school.

Schneiderman began getting calls again to pick him up midday.

The controlled environment at Tennyson had made it hard to predict how or if her son might struggle once he returned to public school, she said.

Partway through seventh grade, an advocate suggested Schneiderman’s son try something different. Evoke Behavioral Health is not a facility school, but a private day treatment program specializing in a type of intervention called applied behavioral analysis, or ABA. Evoke calls itself a “school alternative.”

Denver Public Schools and the family’s health insurance company agreed to pay — despite previously rejecting a similar placement.

“A lot of this feels like dumb luck,” Schneiderman said.

Evoke, she said, has been life-changing. Now that she’s not picking her son up midday, she’s able to work full-time again. And her goofy 13-year-old eighth grader, who loves video games, science fiction audiobooks, and skiing with his parents, is thriving.

He does ABA — which Schneiderman describes as “work-reward, work-reward” — eight hours a day and has both a one-on-one aide and a caseworker. He’s able to do schoolwork for 20 minutes without getting upset, and he’s working on not arguing with his teacher.

His meltdowns now happen once a month instead of five or six times a week, she said.

But that progress means his time at Evoke is coming to an end.

Because he’s doing so well, Schneiderman said the school district wants him back in public school. That probably means Thomas Jefferson High, which offers the same type of small program he had at Merrill — but in an even larger school with about 1,300 students.

“As a parent, that is terrifying. Absolutely terrifying,” Schneiderman said. “There’s no in-between options that we can find. We can’t figure out what our next step is.”

KFF Health News’ Rae Ellen Bichell and The Colorado Sun’s Erica Breunlin contributed reporting.

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.