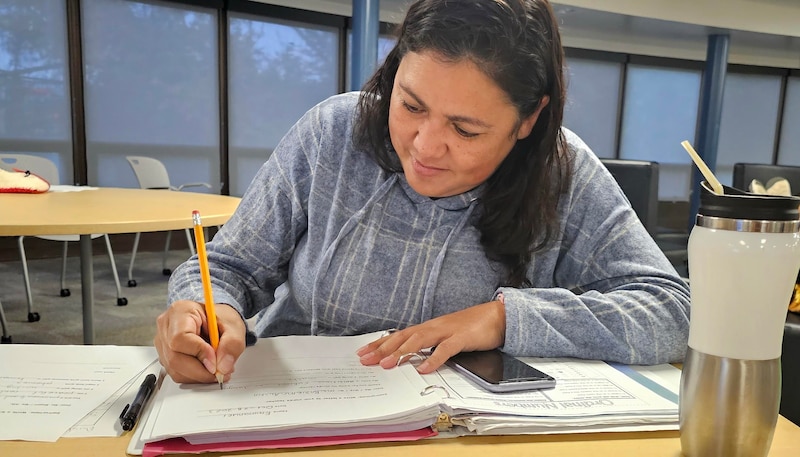

A book, a pencil, and an English dictionary.

For years, those are the tools Carmen Nolasco used to study English on her own after immigrating to the United States from Mexico.

Occasionally, she said, she offered to teach Spanish in exchange for English lessons.

But she had never formally learned English from a teacher in a classroom until her son’s school invited her to do just that in June.

The program at Enlace Academy — a westside Indianapolis charter school where more than 80% of families speak a language other than English at home — serves students’ parents and family members, teaching them English using the same phonics-focused methods found in the school’s elementary classrooms.

Funded through federal emergency monies and a new $3.3 million state grant, the program is one of only a few in Indiana open to adult English learners at all levels of literacy — including those who don’t have a background in reading and writing in a first language.

The goal for the school is twofold: To help parents learn English, as well as give them the tools to work on literacy skills with their students at home. Parents, aunts and uncles, and cousins are drawn to the classes not just to learn English for themselves, but to connect with their students, teacher Megan Singh said.

Schools can be ideal starting places for engagement programs for immigrant parents, said Katie Brooks, a professor at Butler University’s College of Education, and the best ones will include two-way learning with families as well. While other Indiana schools offered English classes for adults in the past, many of those have been cut back, she added.

A program such as Enlace’s, which is ongoing rather than a one-off event, and involves the school’s teachers, allows for strong relationship-building with families, she said.

“In the cultures we’re serving, collectivism is so important,” Carlota Dall-Holder, Director of Academic Language at the Neighborhood Charter Network, Enlace’s charter operator. “We want to empower families and adults to support this literacy practice, because it’s really going to take a village.”

In the school library on a recent Saturday, alongside a dozen other Enlace family members, Nolasco said the classes have allowed her to better help her third grader with his reading and math, as well as communicate with his teachers and his speech therapist.

For an exercise using an artificial intelligence image generator, Nolasco described her happiness about being in class and learning a new language. The image she chose showed a student cheerfully raising her hand.

“It’s an excellent program for starting a new life,” she said.

Teaching parents to teach their children

Family English, as it’s known to participants, is the brainchild of teacher Megan Singh, who came to Enlace in 2022 with a professional background in adult English education. Classes began last fall at the school, which is in its 11th year.

While working with adults is her passion, Singh said working in an elementary classroom put her in the midst of Indiana’s push to improve literacy through the science of reading. She teaches first and second graders throughout the week, and leads their families through similar literacy lessons on Saturday mornings.

Children are welcome and child care is provided, though many choose to stay with their parents. It’s one of the ways the school tries to remove barriers to attending weekly classes, Singh said, though others like work schedules and transportation remain. Between 25 and 40 people attend each week.

“With adult education, it’s not required,” she said. “Adults are choosing to come every week.”

The families that braved the cold and rainy weather on Oct. 28 began class by filling out letter prompts to their teachers in a nod to the school’s recent parent-teacher conferences: What are you doing well in English class? What do you need help with?

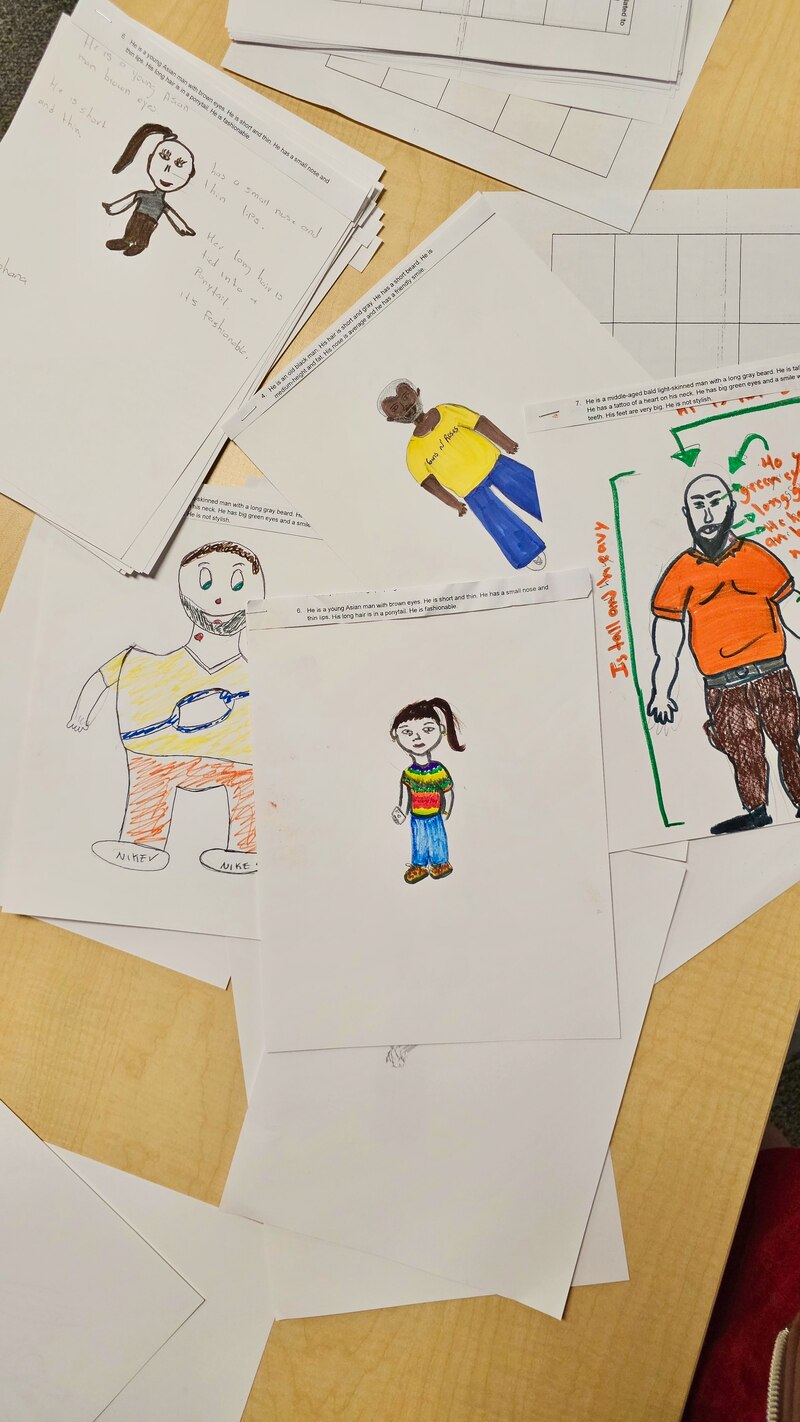

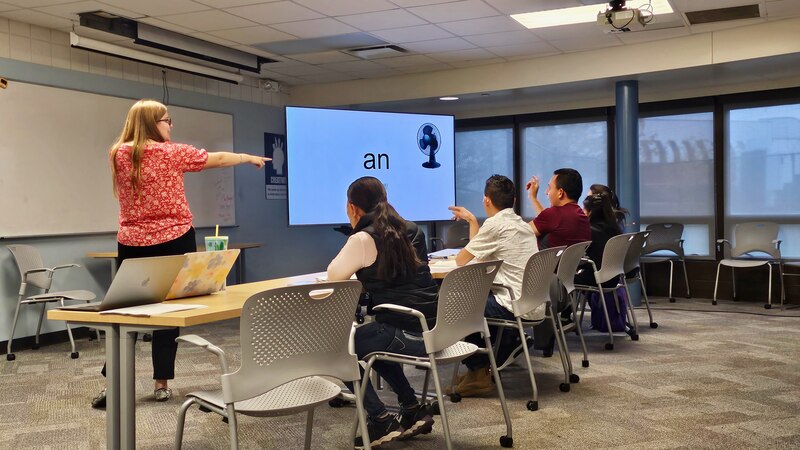

Singh and her co-teacher Ally Hall then turned the focus to phonics in a way that would feel familiar to an elementary student. First the class listened to and wrote down letter sounds — noting the differences in English and Spanish — before moving on to syllables, words, and sentences.

They worked on the endings -am and -an, using their fingers to write out words like fan, can, and yam in the air – a teaching strategy called skywriting.

Some adults can be reluctant to participate in skywriting or other hallmarks of elementary education such as coloring, Singh said. But most come around, especially after the teachers explain the science behind multisensory learning found in methods like Orton-Gillingham.

Singh primarily taught in English, while the students contributed translations in Spanish, French, and Haitian Creole to the words that the class was working on. Hall and two classroom assistants also moved throughout the rows, helping students write out the words they heard: Ham, can, man, van.

“Easy,” said Carmen Nolasco’s third grader, Emmanuel, from the back of the library, where he followed along with the assignment. He was ready for sentences.

School officials hope classes will improve student performance

By teaching their parents, the school hopes to better support students at home, and in turn, improve their academic performance.

Indiana expects 95% of all third grade students to pass the state reading test by 2027. But the statewide rate has stalled at around 82% for the past three years, after dropping 5 percentage points after the pandemic.

Proficiency rates among English learner students statewide dropped 8.5 percentage points from 2021 to 2022, and remained virtually unchanged this year at 64%, prompting alarm from education officials. Around 39% of Enlace students tested proficient in 2023, up one percentage point from the previous year, but down 33 points from before the pandemic.

“We’re not going to get an exemption because our school is 80% multilingual,” said Dall-Holder, the academic language director.

Like all Indiana schools, Enlace must teach reading through methods based in the science of reading under a new state law. But some lessons need to be modified to teach the school’s unique student population, Dall-Holder said.

For example, during a phonics lesson, a teacher might cover the picture of the word on a flashcard in order to help the student focus on sounding out the word, she said. But after the student reads the word, the teacher might reveal the picture to help reinforce the meaning.

“We have to evaluate: If this is what the science of reading is, but language acquisition says this, how do we provide the two so we’re giving students access to both?” she said. “It’s a national problem. It’s not being taken into consideration and it needs to be.”

Immigration creates greater literacy needs

More literacy classes for adults are needed in Indiana as the state sees a growing and changing immigrant population.

Districts like Perry Township have said they expect record numbers of new immigrant students this year, many of whom experienced disruption in their formal education due to political turmoil, natural disasters, or the pandemic. Perry started a program this year focused on helping students with limited English proficiency prepare for the workforce.

Adults, too, need more English language development than before as workforce needs shift from labor to customer service, Singh said.

Though there’s plenty of demand to expand the Saturday English program and open it to the broader community, Enlace officials said they intend to keep it open only to students’ families. One reason is that the school doesn’t have the funding and space to run a whole adult education program, Singh said.

While adult English language classes are available, there’s less support for programs that serve students who aren’t literate in their native language.

The school used federal emergency funding to start the program, and will now turn to a $3.3 million NextGen School Improvement Grant from the Indiana Department of Education to continue and expand it. That expansion would likely be through partnerships with other schools and organizations that could offer their own similar programs.

But funding aside, limiting the program to family members keeps it tightly focused.

“It’s cool to get to know parents and children,” Singh said. “Integrating learning for the student and their family has been very enjoyable.”

As the adult students worked through the listening exercise on the last Saturday of October, Singh demonstrated some of the movements she uses to teach letter sounds to her elementary students.

For V: Teeth over your lips, and then vibrate. For E: Put your thumb and forefinger below the chin to frame the smile that comes with saying the letter. “I” is scratching your nose, like an itch.

“Vowels are difficult in English,” she said to the class.

One student wanted to know: For English speakers too?

“Yes,” she said. “They’re always changing.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.