Voters will soon decide whether to support a property tax hike to pay for improvements at 23 Indianapolis Public Schools buildings — and factors ranging from economic headwinds to a lack of organized opposition could be crucial.

The IPS ballot question, which goes before voters on May 2, seeks $410 million in extra property tax revenue to upgrade and repair school facilities. Rejuvenating buildings and campuses is part of the district’s Rebuilding Stronger reorganization, which aims to consolidate schools and strengthen academic and extracurricular activities amid declining enrollment.

Political science and economic experts say there are a variety of factors that could help or hinder the measure’s passage.

On the one hand, the ballot question comes after months of sharply rising inflation and rising property values that ultimately lead to higher property taxes, both of which could make the referendum a tough sell.

The district estimates that the referendum would generate an extra $3.18 per month in property taxes for a resident whose home is valued at $138,500, what officials estimate as the median home value within IPS boundaries.

“I can’t say whether one would think that bad economic times would have an impact,” said Larry DeBoer, professor emeritus of agricultural economics at Purdue University who has studied school referenda at length. “But the evidence is pretty darn murky from our own history.”

At the same time, powerful political actors that might have tried to defeat the ballot question have so far stayed on the sidelines. Meanwhile, those who want voters to pass the measure appear to be more active.

IPS referendum gets campaign fundraising help

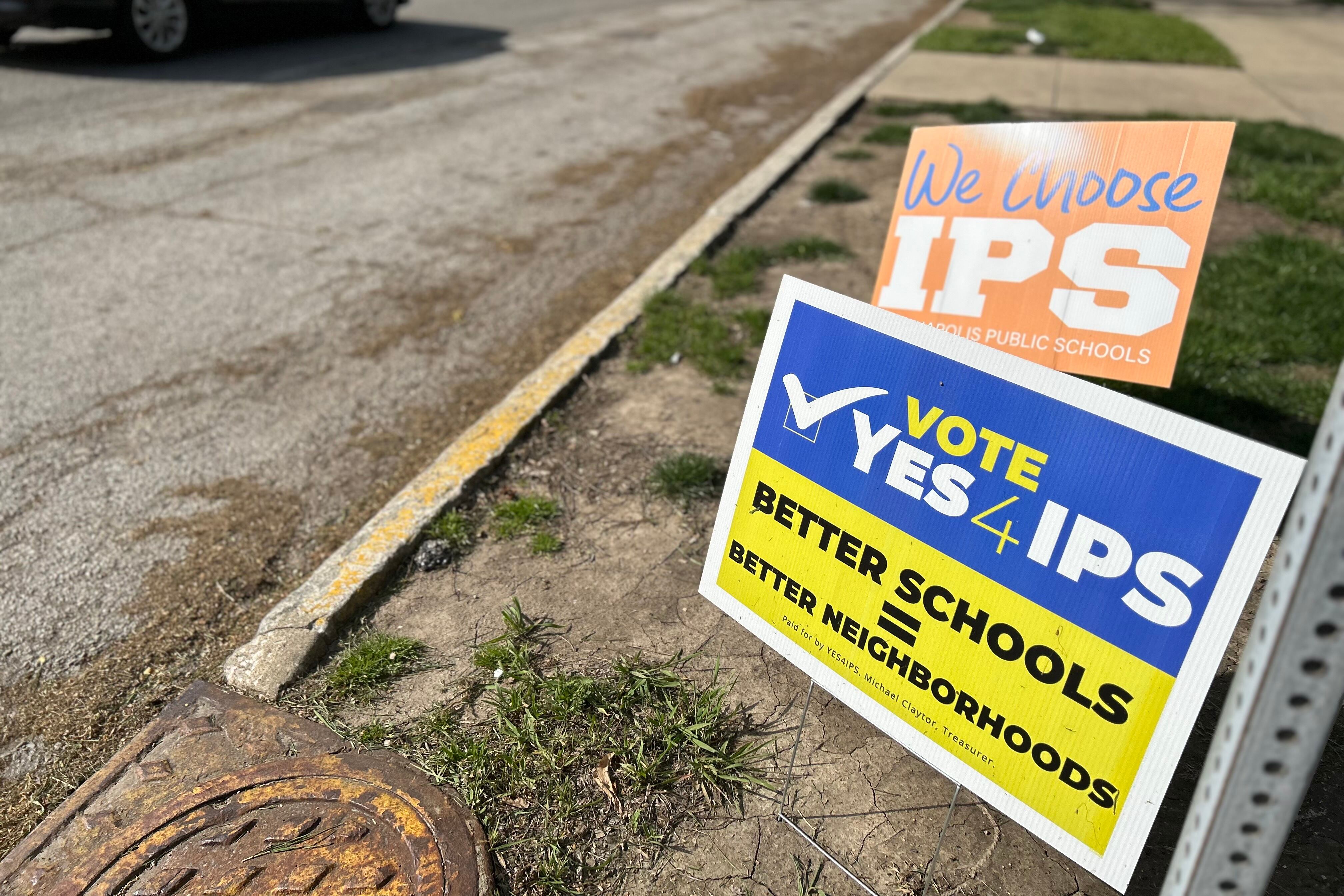

Community members have formed a political action committee called Yes4IPS to drum up support for the referendum. The PAC has raised nearly $69,000 so far, according to campaign finance records.

That includes $12,500 from the Indiana Political Action Committee for Education, the political arm of the state teachers union, and $50,000 from the PAC for Stand for Children, a parent advocacy group that supports charter schools.

RISE Indy, another advocacy group that’s friendly to charters, has also said it supports the ballot measure for capital expenses, although the latest campaign finance filing shows it hasn’t contributed to Yes4IPS.

History might be on the ballot question’s side. Despite current challenges in the overall economy, DeBoer noted that voters approved 16 out of 18 Indiana school ballot measures in June 2020, during the sharp economic downturn caused by COVID.

And the amount that IPS is proposing — roughly 21 extra cents per $100 of assessed value — is also lower than the 25-cent threshold that DeBoer said appears to separate referendums in the state that pass from those that fail.

Still, the money Yes4IPS has raised so far is well below what the Vote Yes for IPS PAC was able to raise in 2018 for the district’s two ballot questions projected to raise a total of $272 million. That PAC brought in roughly $249,000, including $52,500 from the Indy Chamber PAC and $327,803 from Stand for Children, according to campaign finance records.

Previous IPS ballot questions have passed with comfortable margins. In 2018, both ballot questions proposed by the district passed with the support of more than 70% of voters. In 2008, a ballot question for capital expenses passed with roughly 78% of voters in favor.

But past successes should be seen as evidence of IPS officials’ political skills and not proof that the current ballot measure will pass, said Andy Downs, professor emeritus of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics at Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Meanwhile, the influential Indy Chamber of Commerce announced in January it would not support the ballot measure for capital expenses. But it does not appear to be actively campaigning against the measure either. A chamber spokesperson said its PAC has not done any campaigning with respect to the referendum.

And the Mind Trust, which incubates charter schools in Indianapolis, has previously said it will not take a stance on the $410 million ballot question.

The timing of the question during a primary election (when turnout is often lower than in general elections), as part of a municipal election cycle, may also give IPS a boost.

“Oftentimes with these low-salience [elections] it’s just a gut feeling for people,” said Aaron Dusso, associate professor and chair of the political science department at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. “I think generally in Indianapolis, most people [say], ‘Yes I want my schools to be better.’”

Ill will over charter funding doesn’t spill over

The lack of significant public opposition marks a contrast to a separate ballot measure IPS has hoped to put to voters next month.

For months, IPS worked on a ballot measure for May to pay for the academic, extracurricular, and other operational expenses associated with its Rebuilding Stronger overhaul. Yet groups like Stand for Children mobilized vocal pushback to the ballot measure, on the grounds that it did not share money equitably with charter schools.

After the Indy Chamber of Commerce announced it would not support the draft ballot measure, the district pulled the plug, although it later announced it would still move ahead with elements of Rebuilding Stronger.

Stand for Children’s contribution to Yes4IPS comes after parent advocates met in March to discuss the organization’s position on the capital referendum, the group said in a statement.

“Kids 30 minutes away attend schools that are luxurious in comparison and give them huge advantages solely based on their ZIP codes,” Sherry Holmes, a parent at George Washington Carver Montessori School 87, said in a statement via Stand for Children. “Those advantages equal opportunity. I support the IPS capital referendum because our kids deserve an upgrade, and they even deserve more.”

Recent financial relief Indianapolis provided to property owners might mitigate hostility to the prospect of new taxes.

Property owners throughout the city are getting a tax credit to their upcoming bills, an initiative the mayor’s office and city-county council approved using funds with the federal American Rescue Plan Act. The credit is listed as $150 for people with homes valued at $250,000 or less.

“However, that $150 is also just eaten up by inflation and increases in the valuation of property,” Downs said. “Forget inflation at the grocery store — just the value of your property has gone up.”

Early voting at the City-County Building ends on May 1. Eight other sites offer early voting from April 22-30.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.