Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

When Nastassia Tyler attended Lincoln Park High School in 2018, she noticed that her school had an “unofficial” dress code that seemed to be enforced disproportionately on Black and Hispanic girls.

For example, Lincoln Park made students whose shorts were deemed to be too high-cut wear gym clothes for the rest of the day, and security guards responsible for enforcing the policy tended to target “fuller-bodied” Black and Hispanic girls as opposed to their white peers, said Tyler, who is Black.

Tyler graduated from Florida Atlantic University in 2022 and currently works as a firefighter in Georgia, but she still thinks about what she believes were unfair conditions in her high school.

“It was hard to dress sometimes in the summer because it was so hot and the school didn’t have AC, but if you happen[ed] to show too much of your legs or something you’d get in trouble,” she said. “I remember thinking it was ridiculous to control what someone wears in a hot classroom.”

Across Chicago Public Schools, low-income Black students and other students of color are more likely to attend a high school with a dress code, according to data for the 2023-24 school year.

Schools that maintain strict dress codes are more likely to enforce punitive discipline, such as suspensions and expulsions, said Jacqueline Nowicki, a director at the U.S. Government Accountability Office who has published research regarding inequalities in public schools.

Numerous studies show that dress codes are not equally enforced across the country, with students of color being punished for infractions even though they do not commit them at a higher rate. This unequal enforcement of dress codes and other punishments can lead to students of color dropping out of school or having to repeat a grade.

A Northwestern/Chalkbeat analysis of CPS data on the Chicago Data Portal found that 94 of Chicago’s 169 high schools, or 55.6%, currently have dress codes. Of those high schools, 93 have a black or Hispanic plurality of students, while nearly three-quarters of their 104,357 students are listed in the city’s data as “low-income.” CPS defines low-income or “economically disadvantaged students” as students who “come from families whose income is within 185 percent of the federal poverty line,” according to a budgeting presentation for fiscal year 2023.

At all but eight of Chicago’s public high schools, a majority of students are listed as “low-income” in CPS data. Six of the eight schools with low-income populations below 50% do not enforce official dress codes. All eight schools have white populations exceeding 20%, more than double the average white population of 8.78% across Chicago public high schools. Four of the eight schools have a plurality of white students.

Demographic information was not available for two of the high schools.

The rise of dress codes in Chicago

Many schools across Chicago’s South Side instituted dress codes around the early 2000s to prevent students from wearing gang-affiliated clothing, said Lionel Allen, a clinical assistant professor of educational policy studies at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“They no longer had to police what students were wearing or worry if what they were wearing had any sort of gang significance because everyone was in uniforms,” he said.

Current CPS policy bans “overt display of gang affiliation,” but does not specify what gang signs are banned or what constitutes a gang sign.

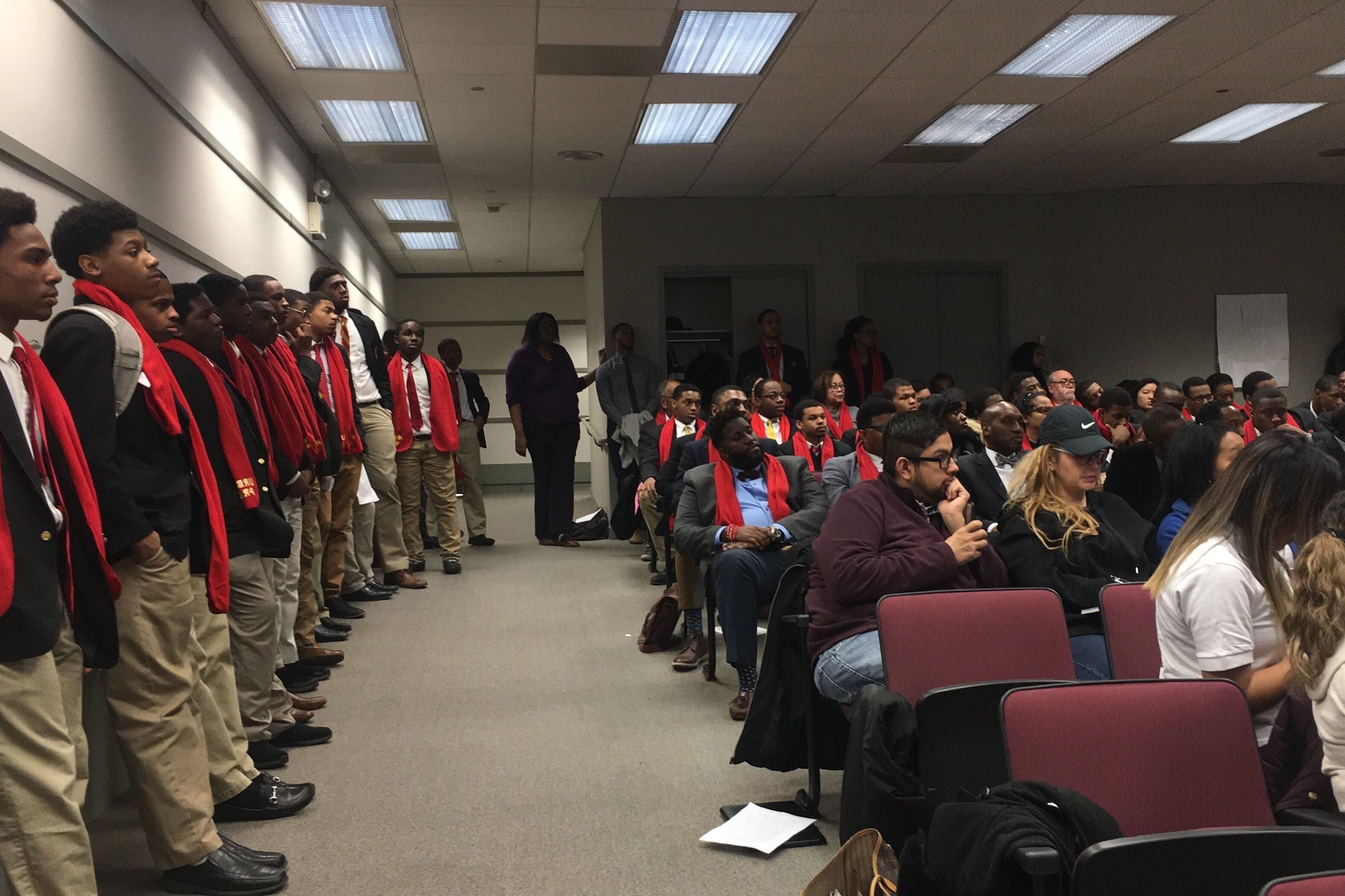

Allen has over a decade of experience as a teacher, principal, and administrator in CPS. From 2010 to 2018, he was the chief academic officer at Urban Prep Charter Academy for Young Men, a system of three all-male schools with locations in the Loop, Englewood, and Bronzeville.

Allen said Urban Prep maintained a strict dress code while he was there, requiring students to wear dress shoes, khaki pants, long-sleeve dress shirts, red ties, and black blazers adorned with the school logo. Allen said the policy was designed to prevent students from wearing gang-affiliated clothing and to cut costs for families on tight budgets – at the time, Urban Prep’s students paid a $150 annual charge for one blazer, one tie, field trips, and curriculum materials.

Urban Prep’s policies were designed to create an air of prestige, and some students who were initially resistant to wearing uniforms came to view them as a source of pride, Allen said. “When people in the street would see the young men walking around with their blazers and ties on, they were applauded.”

But since then, Allen has noticed that some schools in low-income areas of the city have started to use dress codes primarily as a tool for compliance.

Schools can get so preoccupied with enforcing dress codes that they get distracted from teaching students, and the language of some dress codes allows policies to be unevenly enforced, he said in a recent interview.

“Students who attend schools on the South and West sides of Chicago oftentimes aren’t able to come to school as their full, authentic selves,” he said. “They are victims of policies that are more concerned about how they act and their behaviors and less concerned about their intellectual academic development.”

Urban Prep Charter Academy for Young Men did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

CPS last updated its dress code policy in 2022 to prevent schools from banning head coverings historically tied to race or ethnicity, but charter schools such as Urban Prep are exempt and can set their own codes of conduct.

“Chicago Public Schools (CPS) aims to ensure that our District policies are consistently applied for all students and schools,” said Chicago Public Schools spokesperson Evan Moore in a written statement responding to a request for comment. “District and school team members will work together to improve our school dress code and uniform policies to support a safe, inclusive and welcoming learning environment for all students.”

Chicago mirrors national trend

Dress codes and other forms of school discipline have come under scrutiny across the country as recent data has revealed that the policies disproportionately target girls and students of color.

Of public school districts nationwide, 90% prohibit at least one clothing item worn by girls, compared to 69% for boys, according to a 2022 study by Nowicki for the US Government Accountability Office.

A 2018 study by National Women’s Law Center found that Black girls in Washington, D.C. were more likely to be targeted for dress code violations than white girls, and 20.8 times more likely to be suspended from school.

Dress codes often include adults taking measurements of students’ bodies or clothing, which can create uncomfortable conditions for girls in particular, said Nowicki.

“That can introduce some concern around safety when you have adults touching students,” she said.

Public schools tend to disproportionately punish students of color for a variety of reasons, including dress code violations, according to another one of Nowicki’s reports. The report found that 15.5% of public school students were Black, yet accounted for 39% of students suspended from school for all causes between 2013 and 2014.

Allen, the former Urban Prep official, said he also regrets maintaining other restrictive policies while he was principal, such as “silent hallways,” where students were not allowed to speak as they passed between classes.

“Nobody questioned me – as a matter of fact I was celebrated … because it showed I could control African American and Latino students,” he said. “But my job is to educate, not to be a prison ward.”