Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Residents of Montgomery County are grappling with the frequency and vulgarity of antisemitism in their reputedly welcoming public schools.

Kobie Talmoud has been the target of taunts from fellow students who have said things like “Shut up, you Jewish f---” and “Heil Hitler” since he started public school in seventh grade.

Jewish parents also report uncomfortable interactions, which Mara Greengrass prefers to describe as “misunderstandings.”

Greengrass raised concerns after a teacher handed out an anti-Jewish flier from Nazi Germany with no additional context during a lesson on propaganda. But school leaders didn’t seem to understand how a Jewish student might feel if they came across the flier on the school bus, for example. In fact, they seemed defensive rather than apologetic, Greengrass said.

Montgomery County, Maryland, is a diverse, overwhelmingly Democratic and liberal community bordering Washington, D.C. The Jewish population in the region is four times the national average. The county has many Jewish leaders, including the county executive. Synagogues, Jewish day schools, and kosher groceries dot the area.

Yet even before Hamas’s October 7 attacks on Israel, the school district had been wrestling with a disturbing rise in antisemitic incidents that Jewish residents say is unprecedented. And the latest Israel-Gaza conflict has acted like fuel to a fire, with even some elementary-age children reporting that friends won’t play with them because they are Jewish. The challenges the district faces, and its response to them, reflect the difficulties confronting schools nationwide that have grown since the start of the war.

“I’ve never seen a more disturbing time for American Jews than the time we are living in right now,” said Guila Franklin Siegel, associate director at the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Washington, a local advocacy organization that works with the school district.

Echoing Greengrass’ sentiments, Siegel says the district initially reacted defensively when approached years ago about the rise in antisemitism. However, today Siegel acknowledges that the district has become more proactive in its response to such incidents.

With the district’s support, Siegel’s group and the Anti-Defamation League, another national Jewish advocacy organization, have entered schools and trained about 1,500 county educators on Jewish identity, antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and recognizing and correctly responding to implicit and explicit bias against Jews.

The district has also revised the elementary and middle school social studies curriculums to expose students to the Jewish experience, the Holocaust, and antisemitism earlier. It has introduced clearer reporting processes and disciplinary responses, leading to consequences such as suspensions for students committing antisemitic acts. And this summer, officials say they plan to run hate-bias trainings for all staff.

But in the process of addressing the concerns of Jewish constituents, the school district has drawn criticism from other groups within the community. Teachers who were initially placed on leave by the district for allegedly expressing antisemitism in 2023 have been reinstated. Three of them are suing the district for ethnicity, religion and viewpoint discrimination, claiming they shared pro-Palestinian and pro-peace messages that were not antisemitic.

Even the Jewish community is split. Some Jewish parents are uncomfortable with the district’s approach, calling for a clear distinction between antisemitism and legitimate criticism of Israel, and rejecting any move toward censorship. Meanwhile, other parents say the district’s measures against antisemitism have not adequately protected their children.

And it’s not just parents and teachers confronting school district officials. Earlier this month, alongside school leaders from New York and California, Montgomery County Board of Education President Karla Silvestre faced hours of questioning from congressional Republicans regarding the district’s response to antisemitism. The focus of many questions was on the district’s decision not to fire teachers who made pro-Palestinian statements perceived by some as antisemitic.

After she finished testifying, Silvestre was confronted with more questions from Kobie, who was present during the hearing. He and other Jewish residents from the school district met with lawmakers to share their experiences with antisemitism and to press district officials on safety concerns.

Some Democrats criticized the premise of the hearing, accusing Republican lawmakers of attempting to score political points and overlooking antisemitic actions within their own party.

Still, the hearing concluded with a prevailing sense that district officials have lots of work to do.

Antisemitic hate at school rises in diverse county

Jews make up about 2.4% of the U.S. population, but they make up roughly 10% of Montgomery County. Despite their substantial presence — or perhaps because of it — the number of antisemitic incidents in the community has risen recently.

In 2022 and 2023, before the most recent war, police reports describe several school-related antisemitic incidents. Someone spray-painted the phrase “Jews Not Welcome” onto a sign outside Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland. There were also multiple incidents involving swastikas drawn on school property.

Data from the county police department shows that reports of hate incidents for all groups in schools spiked over the last two years, but most of the growth was driven by anti-Jewish and anti-Black incidents. Montgomery County Public Schools experienced a 383% increase in school-based hate incidents from 2021 to 2022. And that only increased again in 2023, with anti-Jewish and anti-Black incidents occurring most frequently.

This trend aligns with recent national data from the FBI showing that antisemitism “drove 63% of reported religiously motivated hate crimes.”

Siegel from the JCRC said the Jewish students her organization is in contact with feel ostracized, exhausted from trying to navigate the war with friends, and fearful for their futures. And she finds herself working with younger and younger students each year.

“Before the last two years, we had not really engaged with elementary school principals and teachers,” Siegel said. “But now we have.”

Student refuses to be his community’s ‘quiet Jew’

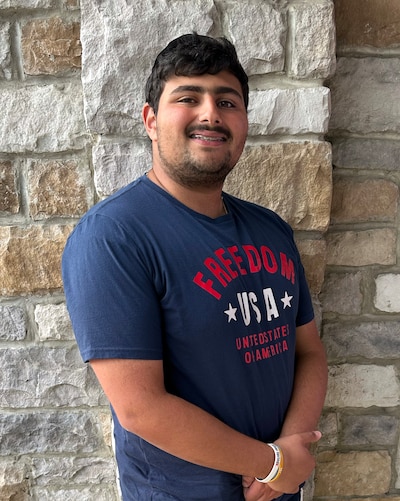

Kobie is engaged on his own mission to educate people in the district.

An 11th grader, Kobie describes himself as an “openly Jewish” and Orthodox. With tzitzit visible at his waist, a yarmulke on his head, and his grandfather’s military dog tags identifying him as Jewish always in his pocket, he has chosen to assert his identity in school.

He’s been greeted in the hallways with shouts of “Jew boy” and the Nazi salute. He’s been called a “Jewish f---” so casually it sounds like a mere descriptor to his classmates. He refers to his peers as “kids” who may be brainwashed by TikTok.

“I feel like you don’t know what you’re saying or doing. They just seemed like idiots,” he said, shaking his head like a disappointed father.

He sees himself as a source of information about Jewish culture and identity for his peers. He volunteers to give presentations on the Holocaust in class, with permission from instructors. He says classmates respond with positive curiosity, asking clarifying questions. He hopes these efforts will help reduce the antisemitism he and other Jewish kids experience.

However, he also has days where antisemitism in his high school makes him want to punch a hole in the wall. And the lack of response from teachers is the salt in the wound, leaving him isolated and disappointed.

What’s taken on additional importance since Oct. 7 is that Kobie is a strong supporter of Israel who thinks criticism of the country often stems from antisemitism.

He speaks up when he thinks teachers are taking sides in the conflict, including reporting a teacher for wearing a keffiyeh, the checkered scarf is considered a symbol of Palestinian identity and resistance.

Kobie associates it with terrorism.

Kobie said that when he challenged the teacher about wearing the scarf, the teacher said: “‘I am representing peace.” Kobie said he responded: “No, you are not.”

“Why should I be the quiet Jew? … If not for me, who? If not now, when?” he said, paraphrasing Hillel, a Jewish scholar from two millennia ago.

Pro-Palestinian messages spur punishments for teachers

Kobie isn’t the only person in the district who refuses to be quiet.

Montgomery County educators frequently take clear political and social stances — openly supporting movements like Black Lives Matter or LGBTQIA+ rights. And alongside the rise in antisemitism, teachers and students who support the Palestinian cause have become more vocal about their views as the civilian death toll in Gaza rises.

However, the district cracked down on this particular wave of educator activism.

Last year, four teachers were placed on leave, then reinstated and assigned to different schools, after sharing pro-Palestinian messages that some interpreted as antisemitic.

One teacher wore homemade pins and buttons that included slogans like “Free Palestine.” She also updated her email signature to include the phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.”

Many Jews interpret this expression as a call for the destruction of Israel and the expulsion or murder of Jews. The teachers said it stands for freedom for all people living in Israel and Palestine, an interpretation shared by many Muslims, according to polling.

“Our teachers did not say anything that was harmful. They did not say anything that was hateful,” said Rawda Fawaz, an attorney representing three of the teachers, who sued the district for monetary damages and to stop them from enforcing policies on the basis of viewpoint, subject matter, ethnicity, and religion, in addition to other requests. “They expressed support for the Palestinian people and they expressed criticism and disappointment in both the Israeli and U.S. government in how they were approaching the situation in Gaza.”

Related: Meet the students who support — and oppose — the pro-Palestinian encampment on Denver’s Auraria campus

Fawaz calls what the district has done “content discrimination,” saying other teachers have made politically charged posts on other topics without repercussions. She also says one of her clients was targeted because she is a Muslim, Arab woman.

A fourth teacher, who is not involved in the lawsuit, was accused of sharing conspiracy theories on social media and denying that atrocities took place on Oct. 7.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights recently issued updated guidance to schools about protecting Jewish, Israeli, Arab, and Muslim students from harassment and discrimination based on nationality or shared ancestry.

The guidance provides examples of when political speech could contribute to a hostile environment at school, such as screaming “terrorist” at pro-Palestinian protesters or yelling slurs at Jewish students during a protest of the screening of an Israeli film. But criticism of Israel or its policies would be protected under the First Amendment — unless it was accompanied by discriminatory comments or harassing behavior, the guidance said.

Explaining the district’s justification for disciplining but ultimately not firing the teachers, Silvestre told lawmakers during the congressional hearing the teachers in question know that if they engage in such conduct again, “there will be deeper consequences, up to and including termination.”

Silvestre also said district officials would be the first to admit they haven’t “gotten it right every time” when it comes to responding to antisemitism, or making Jewish students feel safe at school. But she also said they have made significant changes and intend to continue working with parents and other interest groups to do more.

Balancing support for Israel with backing free speech

But some Jewish parents are wary about the pressures the district is under with respect to antisemitism.

Greengrass, the parent of a recent graduate and a high school freshman, was one of more than 150 former students, parents, teachers, and staff who signed a letter urging the Montgomery County school district to recognize that some Jews welcome criticism of Israel and Zionism, while also fighting antisemitism.

“All Jewish students, no matter their views on Jewishness and the question of Palestine, are entitled to inclusion and respect. Indeed, all students are entitled to such inclusion and respect. This includes Muslim and Palestinian students,” the people said in the letter, which they released before Silvestre’s appearance on Capitol Hill. “We must reject the notion that the safety or comfort of any particular set of students can come at the expense of that of other groups.”

Greengrass knows her views puts her at odds with many members of her community — even sometimes her own husband.

Greengrass has a Black Lives Matter sign in her yard and celebrates Shabbat every Friday night. She does not consider herself religious. She considers herself culturally Jewish and progressive.

She has a strong emotional attachment to Israel and sees it as a refuge for Jews. But she balks at the idea that criticizing Israel or questioning Zionism is antisemitic.

“The problem is that it conflates Jews and Israel, which is exactly what we have been saying everybody shouldn’t do,” Greengrass said.

She also does not believe that expressions of support for Palestinians, like what some teachers have expressed in Montgomery County schools, are inherently antisemitic.

“Statements like ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,’ can mean different things to different people,” she said.

Falling out with friends over the Israel-Hamas war

With discussions, walkouts, and passionate expressions about the war, both Jewish and Muslim students across the country say they are exhausted but hope their schools can still be safe places for them to learn.

That aspiration doesn’t mean all their relationships have survived unscathed.

Kobie, like nearly half of all young adult Jews, says he has cut ties with friends over comments he deems antisemitic about the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Referring to one friend he fell out with, Kobie said: “I blocked her on everything I had with her. … She’s graduating early so, um, bye.” He then dismissively swatted away the thought of his former friend with his hand.

But even with all his resolve, Kobie is also planning to take a break. After graduation, he plans to take a gap year and live in Israel. He then wants to go to college and major in political science.

After the protests at Ivy League institutions like Columbia University, he is not even considering applying to those schools.

Greengrass, meanwhile, remains unsettled about the district’s direction. Two of the teachers placed on leave over allegations of antisemitism taught her son a few years back. She chose not to tell him to spare him from being upset.

She doesn’t feel students, teachers, and the district should approach the issue of the Oct. 7 attacks, Palestinians, and antisemitism with the same reticence.

“You need to be able to say, ‘I disagree with this, but I understand why you feel that way,’” Greengrass said. “That’s how I feel about the teachers.”