Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

A Jeffco school will dramatically scale back a program for older students with dyslexia next year, upsetting parents who say the unique offering has made a profound difference for their children.

Bright MINDS launched at Alameda International Junior/Senior High School in Lakewood three years ago. It’s on the chopping block now because of “inadequate funding and staffing shortages” and will “be dissolved” after this school year, according to a letter sent to participating families last week.

For participating families, including some who commute from outside the district, the news means the end of what’s been a golden needle in a haystack: a comprehensive public school program for students in middle and high school who have dyslexia.

Bright MINDS students will still get some reading intervention next year though much less than most get now. The letter said seventh- and eighth-graders will get only one period of intervention every other day next year, down from two periods daily this year. Other components of Bright MINDS, including sessions to help students with planning and time management, will be discontinued.

Multiple parents said a tense meeting with school administrators on Tuesday left them confused about the rationale for the cuts. They also expressed frustration that the decision has come so close to the end of the school year at a time when school choice decisions are hard to reverse.

In response to Chalkbeat’s questions about the Bright MINDS cut Thursday, a district spokesperson said she’d left a message for the school’s principal, Susie Van Scoyk, to understand the school’s “budgeting choice.”

“Schools have the autonomy through their budgets to determine the staffing and services that are needed to serve their school community,” the spokesperson said by email.

Van Scoyk told Chalkbeat by email Thursday that her team was working on a statement that would not be ready until early next week, citing the school’s graduation ceremony on Friday.

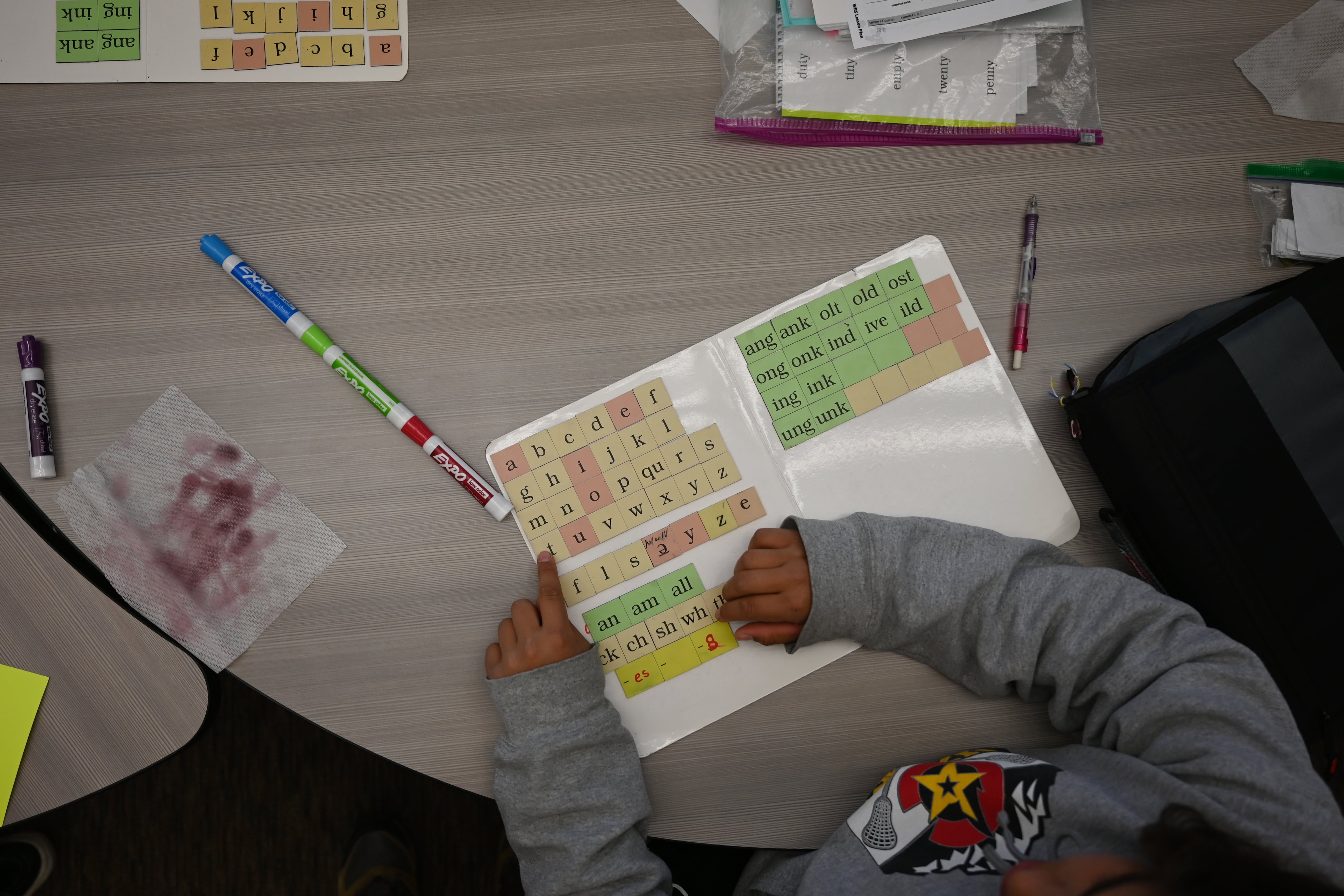

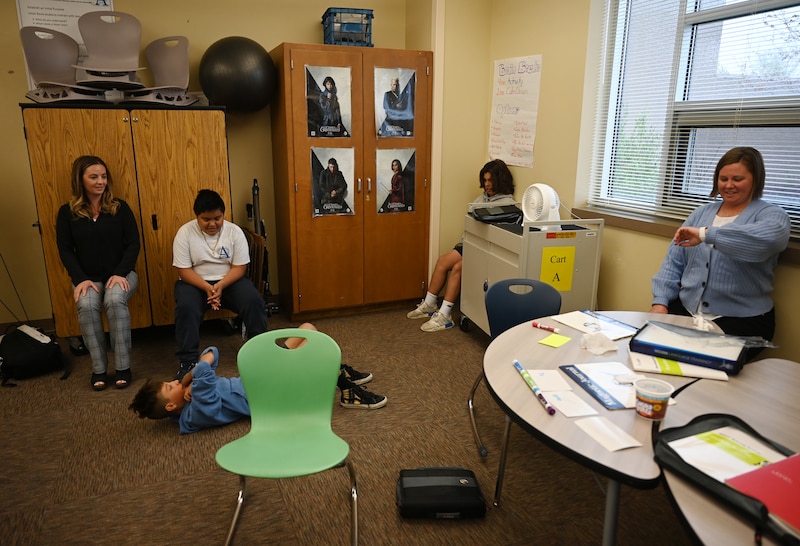

This year, Bright MINDS — the second part of which stands for Multisensory Intensive Dyslexia Support — serves about 20 students in seventh, eighth, and ninth grades. Most receive intensive daily reading instruction plus help with skills like planning and organization, since conditions such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder often co-occur with dyslexia. In addition, Bright MINDS teachers join their students in core classes to ensure they’re getting the help they need to absorb the content.

The demise of Bright MINDS, just three years after it began, comes amid ongoing budget woes in Jeffco as enrollment declines. School officials originally envisioned expanding the program from grades 7-8 to students in grades 7-12. They also hoped Bright MINDS could serve as a model for other schools across Colorado. Former Jeffco Superintendent Jason Glass, who helped spearhead the program, left the district in 2020.

While the state has made several policy changes in recent years focused on better serving elementary students with reading struggles, older students have limited options unless their families can afford pricey private schools or specialized tutors. Students who can’t read proficiently are at greater risk of dropping out, earning less as adults, and becoming involved in the criminal justice system.

Brett Gallegos said Bright MINDS changed his son’s life.

Before the ninth grader began attending three years ago, “He was literally in a ball crying when he would come home from school because he felt so worthless,” Gallegos said.

But Bright MINDS teachers stuck with his son “through thick and thin,” he said.

Recently, his son won an award for making the honor roll, said Gallegos: “It’s a night and day difference.”

It’s unclear how much Bright MINDS costs annually, but it’s primarily run by two teachers and a school psychologist. The 76,000-student district’s proposed annual budget next year is nearly $1 billion. Maintaining mental health staffing levels, increasing substitute teacher pay, and ensuring that elementary schools with certain special education programs have assistant principals are among the district’s budget priorities.

Stephanie Bobian said her daughter called her from school crying when she learned what would happen to Bright MINDS. Bobian said the news was devastating, both because of her daughter’s reaction and because she felt defeated after ”how hard I worked as a parent to find something like this for my child.”

After her daughter was diagnosed with dyslexia in fourth grade, Bobian began a long and desperate search for help. She didn’t have money for $80-an-hour tutoring sessions, but she eventually heard about Bright MINDS through an advocacy group for children with dyslexia.

“To be able to find something like that in a public school … it’s amazing,” she said. “It’s all in one place and free.”

The Bobians’ home high school is Green Mountain, about five miles away from Alameda International. But the commute is worth it because Bright MINDS has helped her daughter, Bobian said. The girl, who also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, was getting Cs and Ds before she started in the program last year.

“She probably could barely read at a third grade level in eighth grade,” said Bobian.

Today, she’s reading almost at grade level and — like Gallegos’ son — making the honor roll.

“She never thought she could be a good student,” said Bobian. “She’s confident now, too.”

Bobian’s younger daughter is in second grade and also has dyslexia. Bobian had hoped to send her to Bright MINDS when the time came. Now, that possibility appears to be off the table.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.