Inside classroom 148, a gleeful Alyce Hartman was telling the tale of three musicians: a squirrel cradling a guitar, a grizzly bear plucking a bass, and a chicken strumming a banjo.

Hartman’s voice rippled like a wave as she read the picture book “I’m Sticking with You-and the Chicken Too!” by Smriti Prasadam-Halls, an author of South Indian heritage.

Twenty-five second graders at Voyageur Academy sat on the floor listening, invested in the plot with every turn of the page.

In the end, the talking animals formed a friendship.

“We make our own music. We’ve nothing to prove. We do our own thing, and find our own groove,” read Hartman, like the storyteller her mother and the gauntlet of children’s theater taught her to be.

Storytime with students is among the hallmarks of Birdie’s Bookmobile, a pop-up literacy initiative launched in 2022 by Hartman.

Through vivid storytelling and mini-book fairs, Hartman increases children’s access to physical books and promotes the pleasures of reading, which could shape a student’s future success beyond classroom walls.

“We want kids to come in and have the opportunity to look and to touch and to feel and to experience” the books,” she said.

In Detroit, many students still struggle to read. The ongoing crisis has lasted more than a decade, angering community members and putting pressure on school officials to reverse the trend.

In the 2022-23 academic year, Detroit’s traditional public and charter school students slightly improved their reading scores on Michigan’s standardized test compared to the previous school year. Yet these results fall well below statewide numbers.

Hartman, a 55-year-old STEM and drama teacher at Detroit Prep public charter school, hopes to spark magical thinking in young readers. She believes books are portals to creativity, cultures across time, and place and potential careers.

Each week, she’ll hit the road and deliver hundreds of diverse books to classrooms, after-school programs, nonprofit organizations, and police precincts in Detroit.

Hartman said she’s also installed little free libraries at Nichols Elementary-Middle School, Detroit Enterprise Academy, and other sites.

“I want children here in the city to really enjoy reading as much as I did,” she said.

A magical girlhood

As a child, Hartman relished the joys of playing pretend.

She transformed into characters from “Pippi Longstocking,” “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” and “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” among the abundance of books inside her Worthington, Ohio home. She loved reading with her mother, a kindergarten teacher. She wrote stories to her grandmother she’d send through the mail.

“I think that’s what has really spawned a lot of this,” she said.

In the early 2000s, Hartman moved to Detroit from Los Angeles, yet those childhood memories enriched her life’s purpose, fostering a love of creativity. Hartman chose the name “Birdie’s Bookmobile” for its cute imagery and alliterative sounds.

To date, Hartman said she’s distributed more than 16,000 books, made possible through grant funding from United Way for Southeastern Michigan, the Holley Foundation, and the Junior League of Detroit.

She’s purchased books from local sellers like 27th Letter Books in Southwest Detroit and Next Chapter Books in the city’s East English Village neighborhood and accepts book donations.

Many of the books Hartman picks feature Black and brown characters, written by a variety of authors, including everything from a humanitarian and a politician to a famous painter and professional wrestler.

Some of the titles Hartman curates have appeared on banned book lists that often target literary works by writers of color and LGBTQ+ writers. Although book bans have surged, Hartman hasn’t received any pushback.

Children of color, literacy experts say, are still overlooked or stereotyped in mainstream culture. Diverse books can teach all children to be empathetic toward people who are different from them. They can also boost a child of color’s sense of self.

Igniting Imaginations

The habit of visiting the library, Hartman said, is becoming a lost tradition, as school librarians and school libraries have begun to disappear.

“When I was growing up, that was special,” she said. “We just don’t see that so much anymore.”

In the wake of such scarcity, Hartman’s poised to boost reading culture. Her mini-book fairs, a feast of illustrated covers, showcase a plethora of stories waiting to be chosen.

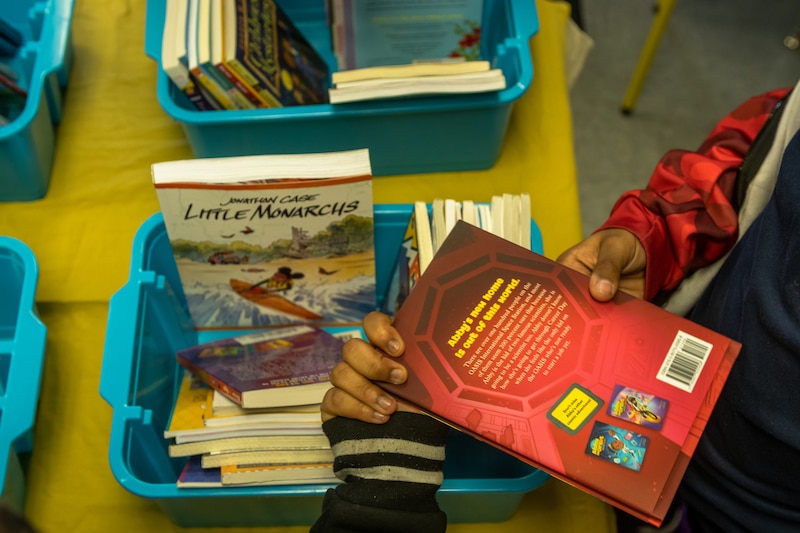

Once the reading was finished, elementary, middle and high school students picked out their own books arranged in baskets and bins atop tables covered in mustard-yellow cloth. A bushy tree with googly eyes covered a wall and conveyed a message matching Hartman’s purpose written on its trunk: “Watch Us Grow!”

A boy huddled with a group of buddies to flip through a picture book starring Nelson Mandela. High school students gravitated toward graphic novels. Students can keep the books and take them home.

Room 148 is Voyageur’s reading cafe, where teachers hold small group lessons. Dayna Peoples, a reading specialist, oversees the cafe. Peoples helps students learn, pronounce and write words, leading the school’s K-8 reading intervention programs.

Voyageur is a K-12 charter school located on the city’s southwest side. The campus has two buildings. Roughly 1,300 students attend.

The school doesn’t have a library, but the reading cafe has more than 500 books thanks to Birdie’s Bookmobile’s recent visit.

Peoples met Hartman during a call organized by 313Reads, a coalition focused on improving literacy access in Detroit. Thrilled by the bookmobile concept, she welcomed Hartman into the school.

“Some parents don’t have vehicles. Some don’t have time to take their kids to the library. In this way, the library comes to them,” Peoples said.

Eighth-grader Kai Fee marveled at “The Gilded Ones” by Namina Forna, who grew up in Sierra Leone before moving to Atlanta. On the cover is a portrait of teenage warrior Deka, clad in gold jewelry and armor.

The 13-year-old noticed the warrior’s long braids, saying “Black girl magic.” She picked Forna’s young adult fantasy novel, wondering if that warrior was just like her.

“As Black girls, we don’t get very much attention,” she said. “I feel like this could help me. Like, believe more in myself.”

Sporting a purple beanie emblazoned with the ghostly Pokémon Gengar, high school senior Tyler McKinnon scooped up two books wrestling with themes of war.

Sometimes, the 18-year-old can’t find books that entice him. He appreciated the variety Birdie’s Bookmobile provides.

“I like reading, even news articles that help me like, not be ignorant, and expand my knowledge,” said McKinnon, holding the graphic novel “The Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees” by Don Brown.

He said he wants to be an informed citizen of the world.

A shining mission

In the afternoon, Hartman went to 27th Letter Books to retrieve another haul of whimsical titles. Nestled on a low-key corner of Michigan Avenue and 25th Street, the bookstore carries historically underrepresented authors.

She greeted co-owner Erin Pineda, who recommended a picture book celebrating body positivity called “Bodies Are Cool,” written by Tyler Feder.

While Hartman shopped, Pineda’s rescue dog Chai sniffed around. Pineda thinks she’s a pit boxer, but her true breed is unknown. Hartman follows the children’s lit scene with zeal.

“I literally haven’t read an adult book in a long time,” Hartman said. “It takes me a long time to go through them now because I’m reading so many children’s books.”

Pineda grabbed “Parker Looks Up: An Extraordinary Moment,” a story she cherishes. Written by Jessica Curry and Parker Curry, the picture book profiles a young Black girl’s trip to see a painting of First Lady Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

In 2019, Pineda helped organize a reading of the book by its acclaimed illustrator Brittany Jackson, a native Detroiter. She met Hartman during the event’s planning meeting at The Commons, a cafe, laundromat and community space on the city’s east side. The two immediately clicked.

The bookstore fuels Hartman’s mission.

The owners have set up a program where customers can round up their purchases to the nearest dollar. That extra money gets funneled into a fund allowing 27th Letter Books to sell Hartman books at cost.

“The work that Alyce is doing is so critical in getting books into kids’ hands,” Pineda said. “Letting them know they deserve those things.”

Last spring, a fire destroyed Hartman’s old ride: a little bus. In the meantime, Hartman drives a van to transport books to the city’s children. This calling, Hartman believes, was bestowed by a higher power.

“This is a vision that the Lord gave me,” she said.

Hartman went to the cash register and paid for her haul. The transaction produced a receipt several feet long. She carried boxes filled with books and loaded up the van. Her next stop: a youth boxing gym.

Before driving off, Hartman took a moment to find the next two books in “The Gilded Ones” series. She wants to give them to Kai.

This story originally appeared in BridgeDetroit and Detroit PBS.