Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

This article was originally published by WFYI.

Community colleges are often touted as an affordable start for students who aim to earn four-year degrees. And it’s for good reason: The average annual tuition and fees for two-year colleges is less than $4,000.

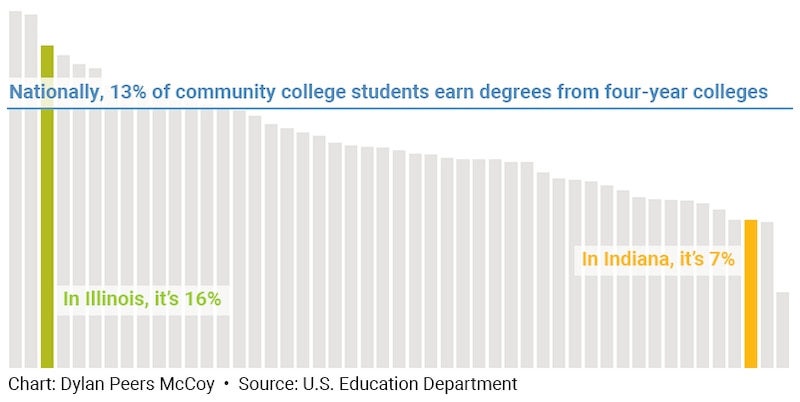

But fewer than 1 in 10 Indiana students who enroll in community college go on to earn degrees from four-year institutions, according to recently released federal data. Indiana has the third-lowest success rate in the country.

“It’s ridiculous,” said Tyre’k Swanigan, a former Ivy Tech Community College student from Indianapolis. “It pisses me off honestly, because I was at Ivy Tech. And this is me. Like, this number — I’m a part of that.”

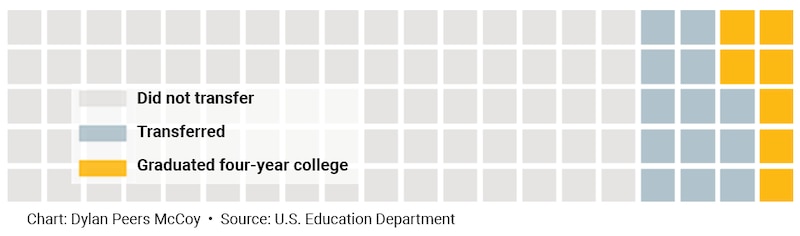

Community colleges offer two-year degrees and short-term certificate programs that can help students get good jobs. But bachelor’s degrees can ultimately lead to higher incomes. And about 80% of U.S. community college students say they plan to transfer to four-year schools.

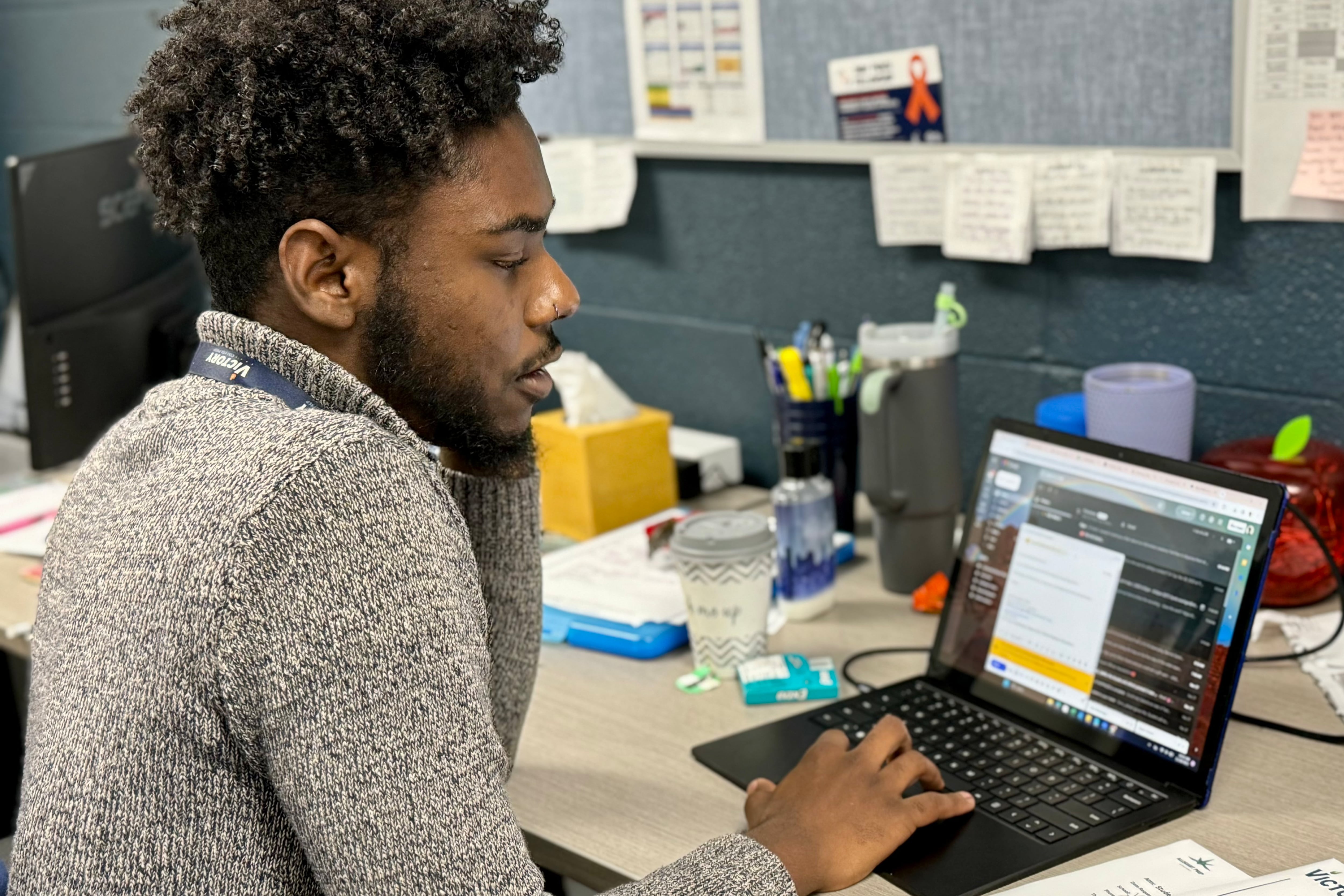

Swanigan, 23, knew he wanted a bachelor’s degree when he enrolled. He started at community college because it was flexible and convenient. “I could still have my full-time job and then make it to my classes on time,” he said.

He did well at first, but Swanigan said he struggled when the pandemic pushed classes online, and he eventually withdrew.

Swanigan’s difficulties are part of a national problem. Last year, the U.S. Education Department released data from students who received federal financial aid. It found that just 13% of those who enrolled in community college in 2014 graduated from a four-year institution within eight years. The rate in Indiana is about 7%.

Community colleges offer crucial access to higher education because they have open enrollment and low tuition. Nationally, community colleges educate about 40% of undergraduates. Those students are diverse — including first-generation college students, single parents, and adults returning to school.

“The community college transfer pathway has long sort of held this potential as a more affordable and accessible route to a bachelor’s and graduate degree,” said John Fink with the Community College Research Center. “More recently, with the sort of increasing costs of college generally, a lot of students have been turning to community colleges as that on ramp to a bachelor’s.”

About a quarter of recent high school graduates who enroll in an Indiana public college or university start at community college, according to the latest state data. The vast majority go to Ivy Tech, a statewide system that enrolled nearly 54,000 full- and part-time students last fall.

Students face challenges when transferring

While most community college students plan to earn bachelor’s degrees, fewer than a third transfer to four-year schools. Students who do transfer still face barriers, like struggling to get credit for classes they already took. And many students don’t get enough advising and support at four-year colleges.

These days Swanigan works in a K-12 school. He wants to help lead a school one day, and he needs a bachelor’s degree to do it. Still, he has struggled to find a college that works for him.

Last year, he briefly transferred to a private, four-year university. That school told him they wouldn’t accept all his community college classes.

Swanigan, who’s gay, didn’t feel welcome at the Christian college, and he withdrew. Now, he’s headed back to Ivy Tech.

Losing credits is a common barrier for transfer students. Neka Booth, 40, returned to school after years working in dialysis because she wanted to become a social worker. Ivy Tech was free for her. And it helped her transition and prepare for a four-year university, she said. “I would tell everybody they should start at Ivy Tech,” she said.

After Booth earned an associate degree in 2022, she transferred to a private college to pursue a bachelors. The new college required her to retake three classes, Booth said.

When students lose credits like Booth did, they’re forced to take extra classes, said Lorenzo Baber, director of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Office of Community College Research and Leadership. That’s time-consuming and expensive.

“That’s money,” he said. “That’s a couple thousand dollars, which matters.”

Indiana lags far behind other states

Experts say that policy can improve success rates for transfer students. Community college students in Illinois are more than twice as likely to earn bachelor’s degrees compared to Indiana, according to the federal data.

Illinois made improving transfer success a priority more than three decades ago. In 1993, higher education leaders created a statewide “articulation initiative” to help students transfer without losing credits. More recently, state law has pushed institutions to grant transfer credit and guaranteed admission to four-year public colleges for qualified community college transfer students.

But even in Illinois — one of the top states in the nation — only about 16% of community college students earned bachelor’s degrees, according to the federal data.

Experts say one reason why improving transfers is challenging is because many community college students have responsibilities outside the classroom.

If students need to care for their family or have a medical problem, that can derail their education. For states to improve college completion rates, they need to support people throughout their lives, Baber said.

“You could have the best designed programs,” Baber said, “but that gets rendered meaningless if somebody needs to stop out because they need to take a job to pay the bills of their household.”

State pushes to improve degree rate

Indiana leaders know there’s a problem, and they have made policy changes to make it easier for community college students to earn four-year degrees.

In 2013, lawmakers required state colleges and universities to create transfer pathways for students who complete associate degrees. If students earn associate degrees in nursing at Ivy Tech, for example, they can transfer to a public four-year university without losing credits, said Mary Jane Michalak, vice president of legal and public affairs for Ivy Tech.

“Whenever possible we direct students into those pathways,” Michalak said, “because by state law then those credits are supposed to transfer seamlessly as long as it’s within the same program.”

There’s a similar program, known as Indiana College Core, to help students who take a year’s worth of classes at community college or while in high school.

Ivy Tech has also worked with universities to make transfer easier. In February, Ivy Tech announced its latest partnership: dual admission to Indiana University in Indianapolis. The aim is to connect students to IU, with counseling and events, while they earn associate degrees at Ivy Tech. Similar models have been successful in other places.

During a recent interview with WFYI, Indiana Commissioner for Higher Education Chris Lowery pointed to the Ivy Tech and IU Indianapolis partnership and the state’s focus on transfer pathways as examples of how the state is tackling this problem.

Because the new federal data followed students for eight years, the people it tracked started back in 2014. Michalak said it doesn’t capture the impact of the improvements the state has made.

“Ten years is a long time,” Michalak said. “There have been a lot of changes since then, both in state law and in the operation or in the administration of institutions.”

But the transfer system is still complicated and it can be hard for students to navigate.

A spokesperson for the Indiana Commission for Higher Education said the office plans to release data on transfer students in the near future. When that data comes out, it will be the first time in more than six years that the state publishes details on how many community college students transfer and complete four-year degrees.

Without that data, Indiana doesn’t know whether policy changes are working.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org.