Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Thanks to an infusion of federal pandemic relief money, city officials bolstered programs that encourage schools to talk through conflicts with students rather than resorting to suspensions.

Federal dollars now represent about $8 million of the program’s roughly $13.6 million budget — funding that is set to expire this summer. Mayor Eric Adams recently allocated more than half a billion dollars to save several other education programs that were financed with one-time federal money. Restorative justice was not included.

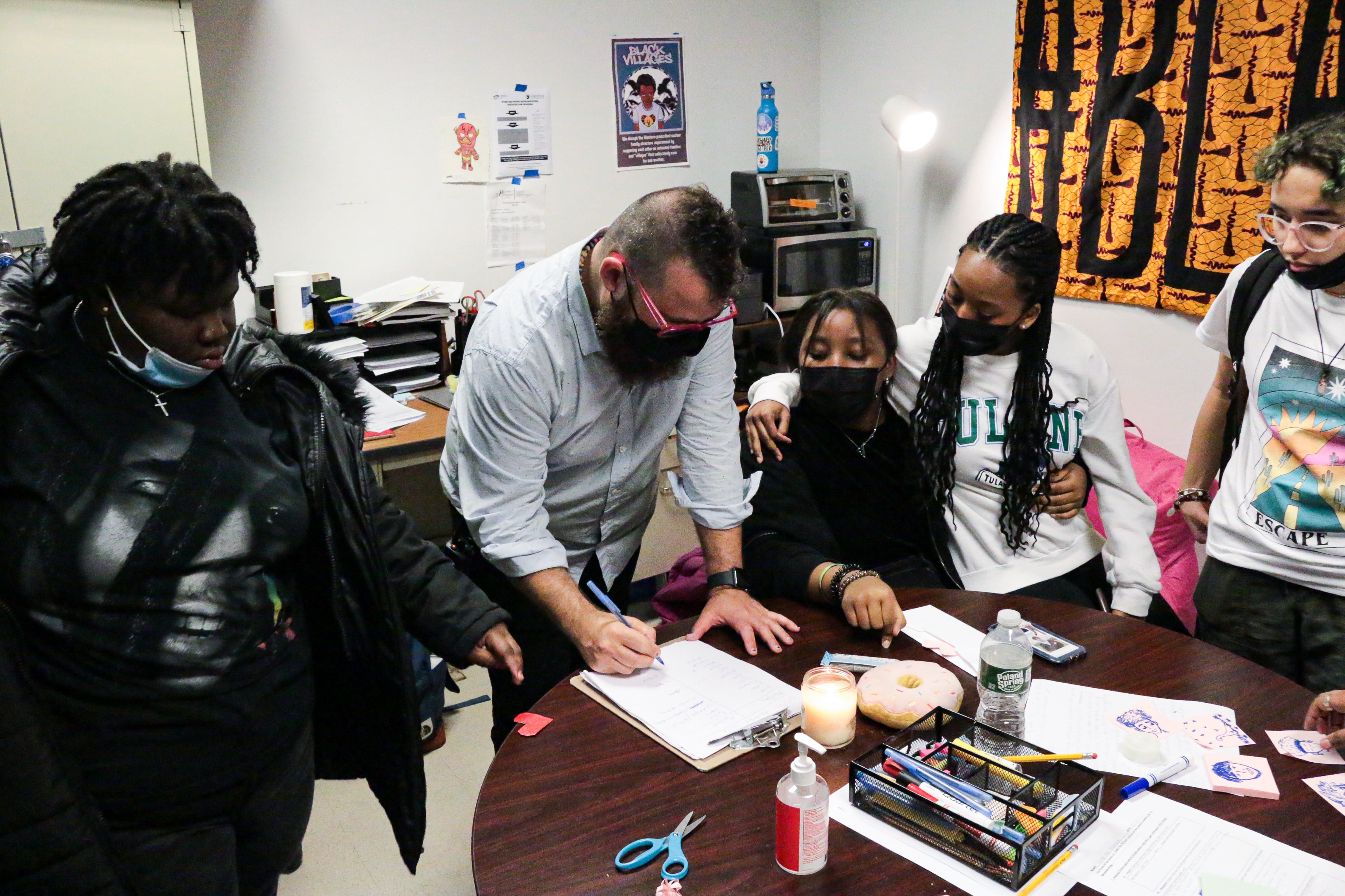

Restorative justice initiatives, which prioritize peer mediation and other forms of conflict resolution, have been a key alternative to more punitive forms of discipline, advocates say. If the funding evaporates, they worry schools will increasingly respond to student misbehavior by removing students from their classrooms.

Those programs allow “students to resolve conflicts on their own and it keeps them within the school community,” said Naphtali Moore, a staff attorney at the school justice project at Advocates for Children, a group that has pushed to find new sources of funding for programs that received one-time federal dollars. “You’re also building relationships as well.”

The possible budget cuts come at a precarious moment: Concerns about student behavior have intensified in the wake of the pandemic, and suspension rates are on the rise, returning to pre-pandemic levels last school year. Education Department officials have not released suspension data for the first half of this school year, despite a city law requiring they do so by the end of March and several requests from Chalkbeat for the statistics.

Schools Chancellor David Banks previously said he does not favor “zero tolerance” approaches to school discipline, but has also stressed that misbehavior must be met with consequences. In congressional testimony last week, he said that the city swiftly suspended 30 students who engaged in antisemitic incidents as some campuses grappled with upheaval related to the Israel-Hamas war. The schools chief has faced pressure to address broader safety concerns on many campuses, as the number of weapons confiscated in schools surged in the wake of the pandemic.

Banks has not pursued formal discipline policy changes, but school leaders across the city received training this year that reinforced their discretion to suspend students, three principals said.

“The message was, ‘if you need to suspend students you can do that’,” said one Brooklyn high school principal who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. “The tone was kind of different. When we first came back from the pandemic, it was more, ‘focus on restorative justice.’”

Advocates fear that the city may retreat from restorative justice programs. Those efforts gained steam under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, who overhauled the city’s discipline code and presided over a significant drop in suspensions. Some educators contend those reforms created more chaotic classrooms in some cases.

This is not the first time restorative justice programs have faced an uncertain future under Banks. City officials threatened to cut the program’s funding in 2022 only to save it at the last minute. A group of student activists pushed the city earlier this year to dramatically increase funding for more holistic approaches to student misbehavior and mental health challenges, including restorative justice.

“Kids need more support than ever, but in terms of the funding, the support is less stable than it ought to be,” said Tala Manassah, deputy executive director of the Morningside Center for Teaching Social Responsibility, which partners with hundreds of city schools on restorative justice and social-emotional programs.

Uncertainty over funding can make it difficult to offer training earlier in the school year or over the summer when they are more likely to be effective, Manassah added. If the funding is added at the last second, that means training may not ramp up until later in the school year when “folks are already overwhelmed,” she said. “You don’t want initiatives that seem like an add-on or more of a burden.”

Some Education Department staff are already bracing for cuts. “There will be less training, less opportunities for people to form teams and meet after school, less opportunity to pay students” to deliver restorative circles where school community members talk through conflicts, said one central office staff member familiar with the city’s restorative justice programming who spoke on condition of anonymity.

An Education Department spokesperson did not answer questions about the city’s plans for restorative justice funding.

Several advocates noted there’s still time to push the city to find new money, as the city budget must be hashed out with the City Council and finalized by July 1.

“We do have two months to push the negotiations to replace the federal dollars,” said Andrea Ortiz, the membership and campaign director for the Dignity in Schools Campaign, an advocacy group. “The budget’s not done.”

Update: After this story was published, Education Department officials revealed at a City Council hearing that they are spending less federal funding on restorative justice than initially budgeted. Officials allocated $8 million in federal funding for restorative justice this school year, not $12 million.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.